Alongside my desire to log off, I’ve been rediscovering something I never thought I’d return to: being a photographer. The whole thing sort of happened by accident but part of an effort to do more meaningful things with my life, whatever that means, as I figure out what’s next. It’s the same effort that got me to quit Twitter last December and try to regain my life by clawing back against social media addiction. After that, I surprised myself by picking up my cameras for the first time in years. I remembered how enjoyable photography can be. But I also recalled old feelings about my photography and the medium at large which led to realize how vulgar photography is.

Photography is perhaps one of the lowest forms of art. Still art, but a heavily debased medium, because of its widespread application outside art and its ability to trick people into thinking they’re viewing reality rather than something created by someone. People don't take photography as seriously as painting or music or sculpture because it’s so versatile. While it’s used to make fabulous artistic works, it’s also the stuff of brochures and billboards and it’s also something we all do, now more than ever. Because of its near universality, the art of photography is underappreciated and the skill required is misunderstood, even while the knowledge required is less than other fields of art. There’s the old axiom of “those who can’t do, teach” and in art, it feels more pointedly that “those who can’t draw (or paint or do anything else in the visual arts), photograph.” Maybe that’s disingenuous to the craft of photography and fuels its debasement, but there is some truth to it. The iPhone age of photography enables an ease with which to produce a competent image because of the magic of computational photography. There’s still a skill to framing, finding the “right light,” and so on, but it’s not quite the same as conjuring up an entire composition from scratch with a pencil or brush or mouse, or even with the buttons and dials of an SLR. Additionally, artists often dabble in or use photography as a jumping-off point to something “greater.” Stanley Kubrick was a photographer first, and the photography-to-movie pipeline is real. There was a point in my life where I thought about it for myself, too.

But I never dabbled in anything else. Instead, I stuck to the medium of dabbling itself. From a young age, people saw creativity in me despite never being the most skilled (who is, anyway?). One of my childhood best friends was a very skilled artist and I was often jealous of his ability to conjure up something out of nothing. It’s not that I didn’t conjure, but that I relied on pre-existing forms. My creativity existed in SimCity, Lego, and celluloid, forms that people may have picked up on as creative, but aren’t the usual emblems of artistry you expect. Hell, in junior high, I barely passed art class. By high school, I was using photography to get out of doing other creative forms in art class, namely watercolour, which I abhorred. Photography became my medium of choice, no matter how lame it is.

Capturing light with cameras has been a part of me for a very long time, well before I ever took it seriously. As a kid, I was experimenting with compositions that made my dad frustrated because I was wasting his film on summer vacations. Then I got my dad’s hand-me-downs; when he got a camera upgrade, I got whatever he was using before — first film, then digital. I used these cameras to take snapshots at parties before Facebook made it trendy. By high school, I developed an interest in more advanced cameras (DSLRs) and after I got one, I began to consider photography more seriously. I even forced myself to learn with manual exposure and focus. Then I went to film. And then back to digital with the mirrorless trend. And so on.

As much as I position this narrative as uniquely mine (because it is), lots of folks have stories like this because, as much as photography can be debased for its alleged ease of use, it’s a relatively democratic medium. It’s meant to be accessible and has been ever since Kodak introduced the Brownie in 1900, helping to make that company into the eyes of the 20th century.

Of course, the point of this essay is about my regaining photography as an interest and pursuit, which presupposes a loss of it. I lost photography in 2020, when I stopped using my cameras, though the writing was on the wall as early as 2019. Ironically, despite playfully adding “retired photographer” to my social media bios, I never truly stopped snapping away. I was just using my phone instead of my Fujis. I kept at it because photography had become a reflexive habit that was hard to fully set aside. I’d basically reverted to my more careless way of photographing that existed before I got a DSLR all those years ago. So I only stopped being a photographer psychologically, as I couldn’t see myself as one anymore. I was just someone who took photos, something everybody does. This was a safer space to occupy and one my brain needed. It’s also a path I likely would’ve continued if not for how things played out last December, but I’m honestly glad things went where they did. I feel like I’ve become reacquainted with an old friend and regained part of my identity due to this shift.

Losing and finding photography

So what the hell happened last December, I’m sure you’re wondering. Truly nothing that dramatic, but still something that had accidentally dramatic effects. It started pretty simple: I wanted something to photograph with that gave me more of a telephoto range than what I was getting from my iPhone, which only has the wide and ultra-wide lens. I didn’t think I’d miss the telephoto lens I had on my iPhone 7, but I used that more than I ever used the horrible ultra-wide lens Apple put on my current phone.

I’d ruminated over this desire for a while, but what pushed the needle on this issue was planning a trip to Los Angeles and Arizona for Christmas and New Year’s. I was going places that I probably wouldn’t get back to very soon, areas with incredible geography that I wanted to have more versatility in shooting. You know, the layers of the Grand Canyon, the LA skyline from the hills, that sort of thing.

The thought of getting another camera with a zoom lens or maybe a new lens for my Fujis had crossed my mind, but neither seemed terribly appealing. By late 2022, I’d worked myself into a funny situation, one in which I felt like my phone was an integral part of me not because of apps but because it became my camera. If I lost my phone, I could just deactivate the phone and reinstall Instagram, but the photos would be lost unless I’d backed them up (which I always put off).

As I mentioned, I fell out with photography in 2020. By then, there just wasn’t any vigor left in me. I was over photography. I felt like I’d spent the better part of my 20s trying to hone my artistic prowess with the camera and it didn’t get me very far. I’m an insecure person who was bullied and belittled a lot at school and at home, so I have an unhealthy desire to be validated. This is the root of why I wanted success as an artist, to prove to all those assholes who denigrated me for years that maybe I was better than them after all. It’s shallow and toxic, I know, but it’s the truth. I got lost in fantasies about where I thought I’d be by 2015, by 2020, and mapped out visions of the future that never panned out. I’ve spent a lot of time chasing clout even though I’m terrible at it. Clout wasn’t why I got into photography, but it did end up fueling a lot of my decisions.

The only time I was sort of good at the whole clout thing was on Tumblr. I spent a lot of time being annoying and making connections with people, some of whom are still my friends to this day. I developed techniques to help build followings, by plugging other artists on my blog and having contests for free prints when I hit follow milestones. To my credit, Tumblr’s where my largest following to date existed.

My Tumblr following led to some interesting moments in my photographic career. I was being featured in other people’s blogs, having interviews, then in 2014, I was winding up in major publications like the Guardian and being part of group exhibitions and zines. 2014 was my year. It seemed like I was only going to keep going up and find more success and do more amazing things. But, at least in terms of my public-facing career, 2014 was probably my peak. I’m ok with that now because I don’t care about followings anymore, but it weighed on me for a long time.

I don’t know if there was a single thing that caused the momentum to stall out. But 2014 was the culmination of years of work I’d built on Tumblr and it was also a period of transition for me. It was when I switched back to digital after becoming a film person in late 2011. It was when I got my first smartphone. It was when I started a new job. And perhaps most importantly, it was when I started breaking out of my shell and became far more social than I’d been in ages. The number of friends I made that year was dizzying.

My desire to be liked caused me to focus on socialization, which was kind of a detriment to my photographic career. The kind of work I was doing also began to shift. I wasn’t doing the straight up-and-down street photography that people’d come to expect of me. I dabbled, sure, but I was moving towards some ersatz New Topographics type of photography by mid-2015, which is a hybrid of street (minus the candid people photos) and urban landscape.

Part of this came from my rethinking how I felt about the morality of street photography. It’s still something that I grapple with, but it’s easier now that I’m not emotionally embedded in the conversation. For what it’s worth, at face value, I still think street is an interesting genre of photography when well-executed. The results often produce intriguing portraits of times and places, two things I’m very much interested in. But the way these portraits are produced makes me a bit uneasy, because of how invasive it can feel. Legally, you might be able to take photos of whatever you want in public, but you also don’t expect to have some asshole with a camera come up to you while you’re on your lunch break and take a photo. And many people have very valid reasons for not wanting strangers to photograph them. These weren’t things I thought of or cared about when I was a street photographer. All that mattered was my craft.

But, even when I was embedded within it, street photography YouTube videos by people like Eric Kim (lol) filled me with anxiety anytime I watched him snap away. So this is what I must look like when I take candids, I figured. I also saw how other street photographers would talk or interact in public and it overall seemed obnoxious. There’s an arrogance and entitlement that I still find off-putting, a far cry from how I felt when I first came across the genre through Vivian Maier (how 2011 of me). Not every street photographer acts like this, but it’s common enough and it makes me question the motives of those photographers, probably not dissimilar to those objecting to being photographed. As Susan Sontag once wrote, “to photograph people is to violate them” and nowhere is this more obvious than in street photography.

Still, I look back at my photos during my peak “streettogs” era (2011-2015) and, not to sound conceited, but I did have a knack for it. It might’ve been my most creatively interesting period. Or maybe that’s the nostalgia talking.

And it’s not like my photographic career was found dead in a ditch on January 1, 2015. Back then, I was still riding the wave of 2014 and the change wouldn’t become apparent for some time. Between 2015 and 2017, I did occasionally get published and was part of a couple minor group exhibits, but it was soon clear that the momentum was gone.

In early 2016, I decided to embark on my first dedicated photo project — my “Canada” project. This was inspired by the photographers I was looking up to. Instead of Maier, Parr, Frank, and Winogrand that hooked me into street, I was looking to Wenders, Shore, Herzog, and Eggleston, an extension of my New Topographics pivot. A lot of these photographers embarked on cross-country road trips around their country, which was usually the US, back in the ‘70s and ‘80s, to document human-altered landscapes and the social environments they existed within. Feeling inspired, I thought I’d do the same.

The project was meant to be a photographic study of the human geography of the lands now called Canada. I wanted to understand what makes Canada “Canada” and convey that to others, as it’s both the place I grew up within and a place with a nebulous sense of culture. By 2020, I’d mostly succeeded in doing what I intended to with the project. I visited everywhere except the Northwest Territories, some places multiple times, and produced a large body of work that included human-altered landscapes, street portraits, some natural scenes, and whatever other bits and bobs I felt fit the theme. It wasn’t complete, but my “Canada” project was definitely getting there.

Yet despite all the time, effort, and money, this was also probably my flop era if I ever had one. This project was done out of personal interest, but nobody else seemed terribly interested, and over time that became disheartening. I still think many of the images I produced are good, but they never really caught on. I didn’t get the traction I had with my street photography on Tumblr through Instagram and many I talked to about the project didn’t seem to really get it.

So when 2019 rolled around, I was kinda over the “Canada” thing. In mid-late 2019 and early 2020, I also became more politically engaged than I had been in years, and it made me feel almost embarrassed over this project I’d poured years into. Why was I doing a project about a sovereign state whose claim to its own land is illegitimate and stolen and whose government actively engaged in the eradication of the land’s original inhabitants (both human and not)? My project wasn’t really meant to be nationalistic, but it’s hard for it to not be construed that way when the work wasn’t actively criticizing its subject.

It felt bad to continue because even if my intentions were good (like with street photography), there was still something off. And while it’s true that people will complain about anything, and not everybody will appreciate a specific artist’s work, there are certain complaints that’re more valid than others. Good intentions or not, I still felt uncomfortable with what I was doing. I don’t want to be associated with negative work, which makes it a bit ironic that I’m bringing it up here, because I still feel uneasy. But I’m here to paint a picture, so this is relevant info.

By the dawn of the new decade, I was disillusioned with photography. I wanted to abandon it altogether. Over a decade and all I had to show for it are some eras I’m not fond of sandwiched by 15 minutes of Tumblr fame. Pathetic. But I still wanted something to document with and figured my iPhone would suffice and not fuss with editing or anything. It was a way to photograph without feeling the baggage of being a photographer. It was liberatory, in a way. When I upgraded my phone in 2020, the image quality blew me away, and only this further entrenched me in keeping my iPhone as my go-to visual tool.

But, like I said, I needed something with more zoom. I was going to the Grand Canyon, after all! I didn’t like any alternative to my phone. The phone was comfortable. I wanted to maintain a consistent ‘look’ to my images, which can only be provided by using the same or similar gear. I didn’t want a new camera or a new lens for my old Fujis. I hate editing and fiddling around with settings, and with the iPhone, I don’t have to do much of either. I can focus on framing and taking the damn photo. Who cares about aperture, shutter speed, and ISO? Like a yassified Kodak Brownie, with the iPhone, you press the button, and Apple does the rest.

Right before my December vacation, a pal came up with an answer to my dilemma: one of those attachable smartphone lenses. It’d let me keep the phone’s look and convenience while augmenting its abilities into something more in tune with what I wanted. Now, there are a lot of them out there, and most of them suck, but heeding that suggestion, I researched and found a couple that seemed to produce great results.

Unfortunately, it was a bit of a bust. The good-quality attachable lenses were hard to get or would need to be shipped and wouldn’t arrive before my trip. So I went back to square one. I thought about a decent point-and-shoot with a zoom lens and then remembered the smartphone killed that category. All that remains are high end ones that’re the same price as interchangeable lens systems.

So, I went back to Fuji. When I was first looking into options in September, I already looked at Fuji and stopped after I remembered how expensive their glass is. Part of me was relieved at the time because I really didn’t want to use my Fujis anyway. I really just wanted the new iPhone Pro.

Fortunately, this mindset didn’t deter me from looking again in December. I found a relatively inexpensive (and by that, I mean still 3x the price of a Nikon F mount version of the same thing) 50mm-equivalent lens in Fuji’s lens roster and went for it. With it, I dusted off my XT1 and jetted off to Californ-i-a. I didn’t think this purchase would cause a seismic shift, but it did.

It was strange using a dedicated camera again, but nice to have something with zoom. I know what you’re probably thinking — 50mm isn’t that zoomy, but if you’ve been shooting with a 28 exclusively for years (and a 35 exclusively for even more years before that) it sure feels like it. I was still using my iPhone too, and I’m sure I looked ridiculous when using both at the same time. The sparks of enjoyment from using my XT1 started percolating and only exaggerated in the new year.

The joy of photography

Much to my surprise, when I got back to Edmonton in January, I kept using my XT1. Initially, I was really just enjoying the zoomed-in look. But continuing to use my XT1 made my interest in it grow. I started going on walks with the primary intent of using my XT1, but I’d use my iPhone still when I wanted something wide or, more accurately, to share on my Story. Even still, it wasn’t long before I was forcing myself to go on photo walks and not take out my phone, to instead be in the moment with my camera.

There was a bit of a snowball effect going on and I wasn’t sure what my target was at the bottom of the hill. I was just going on vibes alone and seeing what stuck. That being said, in the background of this fledgling shift was my increasing desire to finally do something about my social media addiction. I got rid of Twitter, but knew Instagram was the bigger problem, and figured that, through shifting away from using my phone as my camera, it would be easier to put the phone down in general. It could stay in my pocket, instead of being tethered to my hand and filling me with notifications I don’t want or need.

Then I had a real silly-goose thought: what if I dusted off my crusty Fuji X100S and gave it a spin around the block? In another life, it was my favourite camera, but I was nervous about using it. In late 2016, the camera randomly died on me, which is how I wound up with the XT1. I assumed my X100S, which was my go-to camera for 2.5 years, wouldn’t be resurrected, but quelle surprise, it came back to life. It’s worked ever since, but I’ve been anxious about it dying again at any moment.

Nevertheless, I was curious about how it’d feel to use the X100S after all this time. Despite the battery compartment door being stuck shut from 3 years of non-use, I dusted it off with freshly charged batteries and forced myself to use it — and only it — on a walk. No iPhone, no XT1.

And what a fucking walk it was. A swell of euphoria came over me as I wandered through Oliver and Downtown. I realized that, for the first time in years, I was having fun taking photos. That’s not to say I hated taking photos in recent years, but it was an automatic thing I did out of habit, rather than something I found enthralling.

Many photographers have an ideal camera. Maybe it’s a D4 or a Rolleicord or an SX-70. Whatever the camera is, it has to take the images a photographer wants and, just as importantly, feel the way a photographer wants it to. For me, there are two ideal cameras and they more or less work similarly: the Konica Hexar AF and the Fuji X100 series. I may have enjoyed other cameras, but these are the only two I’ve loved.

I got my first Hexar in early 2013 when I was deep in my film period. The camera is a blazingly fast autofocus rangefinder-style camera with a superior 35mm f2 lens from the early ‘90s. It looked cool, felt cool, and made cool photos. What more could you ask for? The Hexar was compact but still felt substantial enough in my hands and was an ideal street photography camera if you didn’t want to deal with manual focus true rangefinders. Sadly, within 8 or 9 months of use, I noticed the aperture blades on the lens had oil on them, which was leaving “splotch marks” on photos when the aperture was small. Because the camera is fixed-lens, it was hard to fix and when I sent it to a repair shop, they claimed they were unable to replicate the issue and just sent it back to me. I tried buying two more Hexars but they had their issues too. I bought a friend’s Fuji Klasse S around this time but while it could be used in a similar way as the Hexar, it never felt right in my hands.

By Spring 2014, my film lab was closing and while I still intended to shoot film, I decided I needed a digital body to complement my film work. A good friend of mine, whose photo blog was largely the reason I got on Tumblr, was (and still is) a heavy Fuji user; his original X100 was the camera used in the photos that made me captivated by his blog. While I’d looked into Sony cameras too, I knew the only real contender was the then-new X100S. As someone still searching for something like what the Hexar gave me as a photographer, I had a feeling the X100S would be like a digital Hexar. I was still a bit reserved because I was 20 and pretentious, deep in my film snob era, though.

And then I got the camera and, after the sticker price shock wore off, took it out of the box, and those reservations melted away. That spark I felt with the Hexar was there with this new camera and it reinvigorated my joy of photography. The images were good but most importantly, it felt right in my hands. The XT1 is a much more capable camera, but there’s just something about how the X100S makes me feel when I use it, and it’s why I used it so extensively for years, beating it up to the point that it died on me until the manufacturer saved it from the grave.

I forgot about that spark. Years of unrealized futures I’d dreamt about, stalled prospects, followed by a general dissatisfaction with the medium that made me into the artist I am. But I’m back, baby! It was fun to make photos again and enjoy what I was doing, rather than letting it merely be some tic that needed to be satiated.

It’s worth noting that even though my iPhone era was perhaps an artistic low point for me, I didn’t stop learning and growing. I really notice it looking at the photos I’m making now vs 5 years ago with the same Fuji cameras. I seem to have really refined my compositional skills during this time, and the evidence of that is clear from the past couple of years of iPhone images.

But perhaps the biggest upside to my returning to dedicated cameras is that I no longer need my iPhone in the same way. And that’s profound because it feels like my phone has had a stranglehold on me for a while. For a long time, I was keenly aware of how detrimental my phone had become, but I couldn’t shake myself from it because of how necessary it felt due to it essentially becoming my camera. Now I could leave it at home or even dumb it down. Maybe I’ll throw my phone into the river, after all.

In the months since, I’ve decided to stop using my phone to take photos altogether and revert to how I was a decade ago, only taking photos with dedicated cameras. For years, I was taking photos with both because I needed phone pics to post on the go, leading to unnecessary duplication. Why did I do this? Because I needed the dope from Instagram. But this year, I’m done with the rat race of social media. Why do people need to know where I was all the time? Why do I need to spend all day taking photos and then spend an hour curating my story and then spend hours checking back in and getting the hits of likes and comments and views to validate me? It’s honestly exhausting and I didn’t like how, on my trip down south, it pulled me away from the experience of being present for the amazing sights before me. If my Instagram-centric way was a negative feedback loop, my decisions this year, regarding social media and photography, have been a positive one. Using my Fujis again made me realize there was an out to the dopamine loop of Instagram. Now I post my photos on Substack and it’s a lot healthier.

Despite gushing over the X100S and how it reignited a spark I forgot even existed, it’s interesting that I’m using the XT1 more. I really love the 50mm focal length as something entirely different from what I’ve experienced for almost a decade, plus the body has great, tactile dials and a large viewfinder. The X100S, in comparison, has a tiny viewfinder, lacks all of the dials the XT1 has, and there are other quirks like the back LCD screen being a bit fucked (but that last one’s my bad). Also, as much as 35mm was my go-to focal length for about 6-7 years, it was also the only focal length I was using (my first XT1 lens is also a 35-equivalent), so I’m enjoying the variety that the XT1 offers with interchangeable lenses. I even got a proper telephoto zoom lens recently, which is pretty insane for someone like me, so used to wide lenses. I’ve also taken to using the XT1 and X100S simultaneously. I do tend to gravitate towards one or the other on a walk, but it’s nice having a 35 and 50 (or 50-230) to alternate between without switching lenses.

I also forgot how much I love the way Fuji captures light, but now I’m obsessed. Their colour science rocks because of how much it mimics film, without the quirks of actually shooting film. Before, I was so worried about not having perfectly HDR-merged photos that captured backlighting well, but now I look at my iPhone photos and wonder why I stuck with such an obviously inferior format for so long. But, I’m not dwelling on it, and know that I went the phone route for a reason, because without the pivot, I may have stopped photography entirely.

It’s genuinely been a great time re-immersing myself back into photography. In conversation with my partner, I said that this is the first time in years I’ve felt like a photographer. They opined that there’s an interesting intersection between artists and their tools, and with photography, the ways that phones blur that relationship by doing everything for you. Despite wanting something low hassle like a phone, when I do the things I loathe, like dialing in settings and editing, I feel more connected to my artistry. I don’t think this is a prerequisite for every photographer, but I fear it may be for me. It’s not like I want everything manual either — I’m definitely not going back to manual focus if I can help it, but even the ability to have more agency over how an image winds up in the end is huge. I’m creating exposures in a way that an iPhone never would and that’s interesting to me. It makes me light up a bit, seeing the 1 second playback of a photo, where I’ve underexposed a shot and it’s revealed a gritty, contrasty frame that I wouldn’t get with computational photography.

Part of my rediscovery of photography is realizing I don’t care if I wallow in obscurity — I’m over being dictated by algorithms and popularity contests. I don’t want to make photos with public consumption as the ultimate consideration and goal. If I’m “flopping” I don’t need to know. I’m now super aware of how much my feelings of worth, talent, and artistry were tied up in what a manipulative app told me. Instead, I’d rather just make images for myself and those in my life who matter, rather than a slew of strangers. I don’t want to chase clout and worry that my choices are bad, because it’s all hollow anyway — I just want to take the damn photo, to hell with the rest. And that’s pretty fucking awesome to realize. Why do we all want such large followings anyway? All that got us was YouTube apology videos.

The vulgarity of photography

But, not everything’s been peachy. The uninterrupted fun had to end at some point in this rediscovery. I’ve had to contend with a lot of my baggage with photography and deal with the medium’s negative sides. Some of that comes from remembering my past ways of doing things, but a lot of it is just stuff inherent to photography that I can’t stop and I know I shouldn’t let bother me, but it does.

The 21st century hasn’t been great for photography, despite how easy and accessible it’s become compared to the pre-digital days. If you talk to photographers who’ve been doing this for decades, they’ll tell you about the post-9/11 shift. The Western world became more paranoid and suspicious and with that, the public’s attitude towards someone holding a camera changed into something more likely to be viewed with wariness. With the rising popularity of the Internet, people also became more concerned about “where a photo might end up” — an understandable question in the face of nascent technology. This was also the time of real stranger danger about meeting up with people you’ve been chatting with online.

And then there were camera phones and, eventually, smartphones alongside the rise in visual-first social media like Facebook and Instagram. On the surface, these developments meant people were taking far more photos than ever before, due to both the digital convenience and the desire to share, and thus it lead to a boom in people snapping away. There was this neat little window, between 9/11 and the universality of smartphones, wherein a decent photographic revival existed, what I’d call the “Flickr era” of photography of the late 2000s and early 2010s. Social media was new and exciting and digital cameras were getting good enough. Girls took their Sony Cybershot to the club and then maybe developed more of a knack for photography and wound up with a Canon Rebel. People experimented with Photoshop and Lightroom was born. This was also when the first film revival occurred and the last period in which 35mm film held technical superiority over top-of-the-line digital cameras. Lady Gaga was the spokesperson for Polaroid, Millennials told the world #filmisnotdead, and Urban Outfitters shoved cheap, overpriced Lomography cameras at us (actually they still do that).

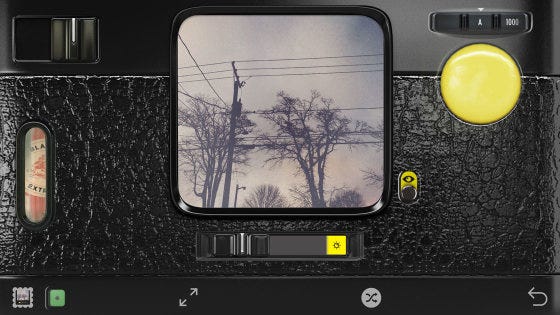

That little window was a special time. It was also when I took up photography in a more serious way, getting my first DSLR, and then migrating onto the film trend a couple of years later. In 2010, Hipstamatic became a fun new photo filter app, aping the aesthetic of film and foreshadowing smartphone supremacy following the introduction of the iPhone a few years prior. By 2011, Instagram got the attention of the photo community and between it and Hipstamatic, iPhones were beginning to be seen as a fun gimmick away from the more “serious” cameras we did “serious” work with. Sort of like a digital Holga.

When 2014 rolled around, the year I got my first iPhone, smartphones were firmly entrenched as the de facto documentary device of my generation. It was inevitable that these small sensor baddies would decimate the camera industry because they were “good enough” if you were only looking at photos on your phone (which most of us were) and it was the camera you always had on you. Unless you were me, because I did actually bring my X100S with me everywhere.

My photographer friends at the time sneered at cell photos. A natural reaction, I suppose. But there was this unquestioned assumption that they were lesser and represented a cheapening of photography, rather than an augmentation or democratization. The fun gimmick of Hipstamatic was over. Looking back, it wasn’t an incorrect take, but the gloss of pretension it exuded was definitely cringe. It didn’t stop the rise of smartphone photography, though, and the medium shifted in the mainstream from a tool for preserving memories into a tool for flexing online to get external validation. And that transformation is even more cringe.

Despite the excessive ubitiquity of photos now, we still are living through an alienating period and so, ironically, I’ve had increasing problems being out with a camera. Photography may be more widespread now than ever, but it’s really only a particular kind of photography that’s widespread: smartphone photography. Look around and you’ll see more people taking photos in public than 10 or 20 years ago but none of them using anything a purist would call a “real camera.”

Society doesn’t condone aberrant behaviour unless it can be exploited for profit. As much as uniqueness and individuality are elevated in our culture, the truth is, there are a set of codes that we’re tacitly expected to adhere to, and we often don’t even realize we’re reinforcing them. The push to conform to set behaviours is something I’ve long felt tension with, especially where cameras are involved. We’re at the point now where simply using a dedicated camera is rare and therefore aberrant. This, infused with the post-9/11 anxiety and alienation, is why I run into problems minding my own business but taking photos in public. I haven’t had many issues in years (aside from being assaulted…twice) because I was just using my phone to take photos, something everybody does. But in the past few weeks, there’s been a couple incidents that left a sour taste in my mouth and have re-ignited a sense of self-consciousness when I’m out with my camera(s).

The first happened before I was leaving Winnipeg. I was photographing the ornate architecture of a well-known historic hotel, the kind that has a million photos of it already. It’s a place that attracts a wealthy clientele and it led to an employee at the institution coming to talk to me because I was making the clientele “uncomfortable.” At the time, I was very polite to the staff, apologized, and said I just admiring the architecture. It wasn’t a tense situation at all — I was even told that it’s fine to take a few photos — and we both left each other at peace after that.

But as I continued on my walk, the situation was being played over in my head. I was obsessing over the word “uncomfortable” and how I was apparently making people feel that way. It led to me ruminating over the common association with photographers as being creepy and rude. I don’t think I was being either — none of the rich patrons were even in my viewfinder and I had no idea nor any desire to document what they were up to. I’m already sensitive to this correlation because of my past and how people used to react and it informs how I try to present in public with my camera now. Generally, since my street days, the issue only arises taking photos of buildings or signs, because I’m interested in architecture and typography. Is there something wrong with that? I don’t think so; to me, it’s a pretty benign activity. But no matter how harmless I am, I’m being read in a particular way that, in Winnipeg, triggered old anxieties to erupt.

And then I got back to Edmonton and something even worse happened. I decided to go to the mall, because it truly is one of the most Edmonton things you can do. I was testing out my new telephoto lens and you really are perceived with that thing on your arm. Again, I’m taking photos of architectural details and nothing else really, but people don’t know that. People assume the worst, even at a major attraction that gets photographed constantly. Eventually, someone from security approached me under the guise of doing a “mall customer survey.” I could tell this was a lie, but I went along with it because I’ve learnt it’s better to not escalate things, and I thought if I entertained them, they’d leave me alone. I embarrassingly gave them way too much information about myself until they finally gave up the real reason they were talking to me. They said what I was doing was fine, but that they just wanted to check in, so it felt like a weird encounter but I continued on my way. Soon, though, I started feeling gross, but before I could piece together why I had that sensation, the same security person found me again and changed tune. They spoke with their superior and said that, in fact, I need permission from the mall to use a “professional camera.” I didn’t know what to say, so I just said “ok” and they left, which is probably for the best, because I didn’t want to interact anymore. After that, I b-lined for the exit because I couldn’t stand being inside that space anymore.

In both situations, I wasn’t doing anything wrong but it didn’t matter. After encounters like this, I often find myself trapped in thoughts like, “what’s the big deal” or “what am I actually doing that’s a problem here?” If you talk to security, there’s never an answer beyond “it’s just the rules.” The most ludicrous thing is that many of these places want you to take photos on their premises. Both places I photographed weren’t obscure, random places; they’re major tourist hotspots and people snap hundreds of photos of these places every day. I’ve been one of those people before and never encountered issues. The mall has gimmicky attractions that carry the explicit intent of posing at while the hotel’s Instagram tags are full of well-coiffed individuals flexing their opulence at viewers. However, this isn’t how I was taking photos — I was doing it in an aberrant way that invites negative assumptions.

Because of Instagram’s ability to commodify literally anything, our society rewards photography, but only if it’s done the proper way. Businesses and institutions want you to take photos, but only with your phone, with the implicit (and occasionally explicit) intent of getting you to post on socials which act as free advertising for them. This is why the gimmicks of instabait interiors exist. Low-res phone pics are non-threatening because it’s universal and mainstream — even though many people do nefarious things with phone pics.

When I use a “traditional” camera to document places, even ones designed to spur photo-making, things can get weird. People get suspicious and you’re viewed as weird. Sometimes people are merely curious or uncertain, and I can explain myself, and all’s good. But what bothers me is when the assumption is that I’m up to no good and no amount of rationality can fix it. Despite how harmless I’m being, I’m being made to feel as if I am doing something terrible, and that perception makes me anxious and feel awful about myself. I shouldn’t let this bother me, but also it shouldn’t even be an issue. Someone with a camera is not, in the vast majority of cases, a threat, and yet certain people treat you as if that’s what everyone with a camera is because they can’t comprehend it any other way. And no matter how rare these instances may be, they’re still bad experiences that weigh on me and add up. Maybe I should just take the same boring photos of Lake Louise. There’s still a few socially-sanctioned places for “real” cameras and it’s one of them.

Painters, linocutters, and graphic designers don’t have to deal with this kind of public scrutiny. That’s what I was thinking about after I left the mall. I shouldn’t either, but I do, because I picked the lowest form of visual art. I know it’s not my fault that this is the way things are, but I still deal with its consequences. It imbues such a distinct discomfort and doubt that hinders my creativity in many ways.

But why don’t other visual artists have to contend with so much negativity? Because, compared to the competition, photography is vulgar. Think about the language we use to describe the act of photographing: taking, shooting, snapping. Never making, creating, or producing, the kind of language other artistic mediums get. This language assumes that photographs are to be something plucked from the real world, rather than something made by a person. It also conjures up images of guns and violence, with subjects being the victim.

But it goes beyond language, obviously — photography as a medium is vapid and low-brow, while its versatility means that it’s not perceived creatively. The assumption when you see a camera isn’t artist. This isn’t an inherently bad way to be read honestly, so I don’t have any real complaints there. But there’s another side of the vulgarity. Not only is it crass and the medium of the masses, it’s also gross, obnoxious, paranoia-inducing, indelicate, and creepy. This is the part that gives me pause and discomfort. With a camera, you’re liable to be called anything from a cop to a creep, and I’ve even been tackled by paranoid folks for taking photos. No matter how much I’m not being malicious or doing anything “bad,” other people don’t know that and many can’t be convinced otherwise. Of course, they don’t know the intent behind other artists either, but the assumption isn’t the same.

This isn’t to say I don’t know why people can be be suspicious. I don’t love always justifying myself, but I recognize where the curiosity and concern can come from, and would rather put someone at ease by explaining what I’m doing than have them continue to view me as suspect. It’s easy for me to get wrapped up in these negative cycles about how photography’s perceived despite them not happening often. But getting tackled once for taking a photo of a building is once too many, if you ask me. Having someone threaten me, rip my glasses off, and throw them onto the ground because I was photographing the LRT and they were paranoid about being in frame is also something that should happen approximately zero times. My most recent bad experiences haven’t been violent, but they’re also in popular, well-documented destinations. I'm completely lost as to why there's a problem since I'm not the only one taking pictures in these places - I'm just usually one of the few using something better than an iPhone 13 Pro Max.

Of course, I don’t think photographers always help matters. A lot of people’s imaginings of photographers are around very real, very negative associations. I can understand why some find it intrusive. That same entitlement I critiqued street photographers for earlier exists in some way in a lot of other photographers, myself included. But it’s different when you’re in a public place, photographing things that don’t carry the same weight in terms of (perceived) expectation of privacy in public. Put another way, it’s one thing to assert your right to be somewhere when you’re photographing random people and another to assert your right to be somewhere when you’re photographing a tree or a building. I’m sure many will disagree with me, because, yes, technically, at the heart of it, you’re asserting the same thing on the same basis, but the human experience demands that they be looked at differently. There’s a fundamental reason I got an adrenaline rush shooting street that I don’t really get photographing architecture.

That’s not to say I don’t think people can’t do street justifiably. It’s part of why I switched to doing street portraits more, to do similar work in a way that feels less prone to being invasive. But even if you’re hooked on candids, having more openness can help. I’m also not sure if being ‘sneaky’ helps people’s impressions, though I understand it has less to do with being caught red-handed and more to do with wanting to preserve the candid nature of what’s being documented. I really like the approach Mary Ellen Mark had when photographing subjects. She often hung out in the same place for weeks, getting to know the people that frequented that area, had conversations, and let people form a trust with her that made them feel more comfortable with being photographed by her. If someone objected, she’d turn her lens elsewhere. That’s obviously a lot of work, but I also think it produces deeper, more meaningful work than the sloppy snapshots of Garry Winogrand or the spectacle of Bruce Gilden. There’s also more purely candid work that feels less invasive and I think it boils down to the style of photographer and how they interact in public. But this is also a topic that I don’t have any final thoughts on, even though I’m thinking a lot about it lately.

Unfortunately, I know the negativity’s not going to change by my hand. I don’t know if there’s a simple solution beyond compassion, something we need more of in our society. In the case of photography, this needs to occur from both sides. Photographers get entitled and crusty because they’ve been put into defensive situations so many times by various entities. Sometimes this is useful, but other times it isn’t. Many photographers don’t stop and think about how their actions are perceived and how to mitigate that (or they’ve learnt to not care). That being said, no amount of mitigation on its own will completely fix the negativity. On a personal level, I’d love it if people stopped assuming the worst just because I have a camera and look like I know how to use it. I’d love it if people didn’t jump to conclusions and become arrogant for no real reason. At the end of the day, if I’m photographing a literal landmark (or any building for that matter), what’s the harm? Like, literally, why is this an issue? It’s often illogical, even if sometimes I completely understand where it’s coming from. You plop yourself in a poor, racialized community that’s heavily policed with a camera in tow and people are suspicious and think you’re the police. I’ve had this happen before and, for some, no amount of convincing changes minds because of how often they’ve been lied to by carceral systems. As much as I would love it for people to believe me and not assume the worst, I get it sometimes. I don’t have all the answers because some of this is much bigger than photography itself. We also live in the supremacy of private property and it makes people very entitled about lines in the sand.

Obviously, I’ve got a lot of strong feelings about photography, both in my own trajectory and how it’s seen and done in the wider world. Unfortunately (or fortunately?) none of this is a complete, final word on photography. And as much as some negative experiences knocked me down a peg, I don’t want them to define me. But I won’t lie — some of these recent bad times have made me spiral and wonder if it’s worth it to go down this debasing path. I worry about getting attacked again, but in more critical ways. Maybe that’s some trauma I need to unpack at some point. I know I can’t let bad experiences weigh me down constantly. It’s exhausting and indulging these feelings too much only causes more problems. So, I think the vibe for now is to keep creating photos because, regardless of how lowly photography is, it’s still a medium I enjoy and I think I have interesting things to say with cameras.

Author’s note: Have you been to this essay before and wondering where the section on AI-generated art is? I realized that, although it’s related to the broader theme of photography, the topic is otherwise pretty disconnected from what I’m going on about here, so I tweaked it slightly and turned it into its own post, which you can view here. Enjoy!

Much to say on this opus. But I will try to stick to the things that really jump out from memory now.

1. Very glad to see you find your love again. I still have one of your images framed on my wall, and I really loved cities and citizens. I think, for some people the logic of all this work doesn't make sense, but the feelings do. I'm personally glad you went back to your fuji and rekindled your passions.

2. I literally could not object or disagree with the entire zoomer take on public spaces. It is NOT an offense to have your photo taken. It is not an intrusion or violation and anyone who thinks it is needs some real problems to deal with. People have gone off the deep end of individuality and gross selfishness to the point of it being nearly disgusting. Combine that with all the sensitive couching you did about peoples right to not feel infringed upon in any way and well, I just flat out disagree with all of it. It's bullshit. We long ago surrendered the lands to corporate interests, we along ago surrendered our rights and our privacy and if you can stand there with a straight face and tell a photographer who is trying to find some romance in the banality of city life, trying to help build an identity for a time and place, trying to make memories--which one hopes will be loved by the very same residents later, is some kind of violation well, I'm not hearing it. Some people's jobs are to be offended, put up on, aggressed, and violated by the very existence of other. There is no saving those souls and I refuse to allow them to come between me and work I think matters when documenting life. Does this mean we need to be assholes? no. But we need to hold the line at the very least and push back against the encroachment against the entirely harmless act of taking photos.

3. that kubrick shot is everything i wish my work could be but never will be. because i am of the age of the jogging pant, the cell phone, the mask. The cheap glass and steel facade. the ugly EV cars.

I had more, but sadly I'm all pissed off again about the whole "I'm trying to be the nicest human to everyone and when they shit on me it makes me question my entire existence" line of thinking, which we've discussed at length. You sir, need more play in your life. you need more jokester energy.

We all end up waste products. Even those who are finest among us, who are nicest, most law abiding, most sensitive to the ridiculous needs of ridiculous people. only some of us will leave some work hopefully worth looking at behind us.