Postmodernism and Vaporwave

The Implications of Post-History

I’ve been doing some redecorating lately and curating interior design inspiration for the future. For interiors, there are two styles I gravitate towards: Mid-Century Modern (MCM) and Post-Modernism (PoMo). But, because it’s just us girls here, I’ll let you in on a secret: I prefer PoMo, controversial designs and all. I think it’s mostly because it’s fun in a way that MCM isn’t and I adore its adherence to nonsense (no, I’m not immune to squiggly mirror propaganda) and references to Art Deco. Even when PoMo isn’t playful, it still tends towards a boldness I find captivating. I also really adore the “cocaine ‘80s” version of PoMo, in all its dark, shiny, brassy glamour. It’s the ‘80s yuppie look and if you still have no idea what I’m talking about: watch Beetlejuice and pay attention to what designs those New Yorkers like turning that old house into (which I’d never do to such an old house — I promise). Or watch Death Becomes Her and American Psycho. This variant of PoMo was the peak of stylish interior design when I was born and even though it quickly fell out of fashion in the 2000s, I’m still nostalgic about it.

It’s not just me, though — PoMo interior design is going through something of a resurgence. I saw the first hints of it in the mid-2010s at Crate and Barrel (my favourite look-but-do-not-buy store), well-known for its updated MCM offerings when I noted brass and copper utensils for sale. But it really became apparent around 2019 with the rising popularity of Structube among Millennials, and now the revival is only stronger with stores like Urban Outfitters completely submitting themselves to PoMo, making Gen Z where this trend is thriving.

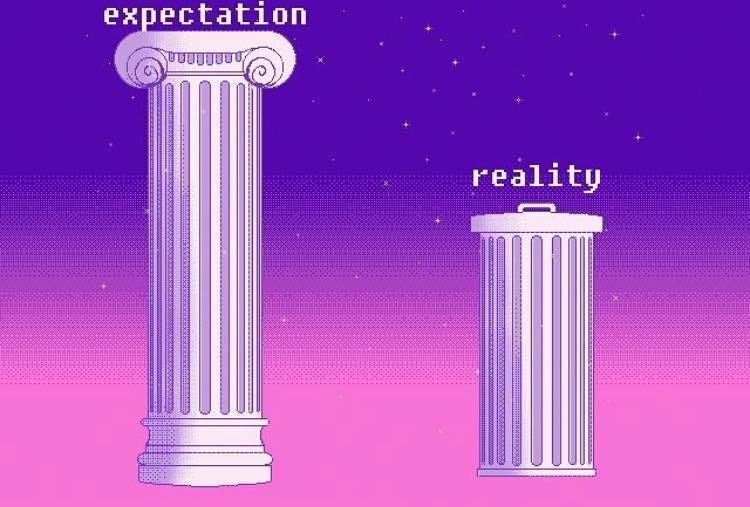

But, I’m not totally into terrazzo and brass because it’s trendy. I’ve liked this style for a while, and truthfully, I’m often annoyed with the current revival because it’s mostly ersatz. Gold finishes are having their best public showing since the mid ‘90s, but it looks cheap. When I think of PoMo, I think brass with a mirror-y sparkle, not what looks like matte spray paint on plastic and metal. The more mainstream PoMo revival (the kind that’s trickled down into HomeSense et al) more broadly feels toned down from what I remember of my grandparent’s place growing up. It lacks the iconic and child-like punches of colour that Memphis brought us, for a more muted and palatable but austere version of what was an intentionally vivacious design movement.

You see, post-modernism, as a broader movement, that’s included architecture, philosophy, film, as well as design, is a reaction to modernism. It’s interesting to see that this is repeating itself now. After 20-ish years of MCM revival in interior design in the early 21st century, we’re back to PoMo because, collectively, we’re tired of teak. Minimalism is over, so we have gold again in our homes, mimicking brass while lacking its sheen.

I know you’re probably wondering what this all has to do with vaporwave. The short answer? Everything. But to start at the beginning, while looking around Etsy for design inspo, I found this Sappho statue that feels like such a serve. Why? Because it’s fucking melted.

This 3D-printed plastic statue is the perfect simulacrum that encapsulates our late capitalist post-modernity, completely unmoored from history itself despite references to it. But also, it’s very vaporwave. You know, that Internet meme from 2012. Or more specifically, an online art movement that gained traction in the early-to-mid 2010s. Most known for appropriating late 20th century cultural artifacts, ranging from elevator music to ‘90s computer graphics, packaged in a melancholic nostalgia that’s perpetually drenched in dusk and neon. Vaporwave is most known as a music genre spawned from digital plunderphonics spoofing ‘80s jingles but it’s arguably as visual as it is sonic. If I had to sum up the vibe of vaporwave into one sentence of references, I’d probably say it’s Miami Vice mixed with Robocop mixed with Windows 95 mixed with an empty Sears about an hour before the mall closes, with the nostalgic perspective of the contemporary world beating us over the head.

Vaporwave is a great example of synthetic memory. No, I’m not talking about Blade Runner, although the movement takes great inspiration from it and other early cyberpunk media. What I mean is that vaporwave produces the idea of a memory in viewers that resembles what we think the past was without being from that past, at least not wholly. But the movement is very clever at making the synthetic feel authentic. It makes new songs feel like something you would’ve heard in the elevator up to your 18th-floor office cubicle in 1987. It makes young people born in the 21st century say that vaporwave feels like being stuck at the Bay even though you’re much more likely to hear Ariana Grande there nowadays than Muzak (but we’ll get to her later).

Vaporwave seeks the past but it only exists because of our contemporary reality. It’s more about the present than the past and drenches itself in a nostalgic aesthetic, not because of the periods it’s referencing so much as because of what came after. Vaporwave is a reflection of postmodernity and its repeated references to the early postmodern period (the ‘70s through ‘90s, with emphasis on the ‘80s to mid ‘90s), which includes the era of PoMo interior design, are due to the anxieties that’ve arisen as a result of postmodernism’s tenets becoming more formidable and worrisome in the decades since. Even when we attempt to superficially touch the authenticity of the past, we’re limited by our pastiche present. So last century’s glossy golden brass light fixtures become our matte-painted gold lamps because we live in matted times.

Vapor101

Vaporwave began circa 2011 as one of the first music genres to emerge devoid of place. It was birthed from the Internet itself, by disparate actors of varying geographic origins, immediately following 2009’s chillwave. Soon, by 2012, vaporwave arguably hit its peak in the cultural zeitgeist, typical of the fast-moving ways of the Internet. This was when Rihanna and Azealia Banks were sporting vapor aesthetics and when the movement reached peak meme status. Because its visual and audio motifs spread memetically, vaporwave was quickly written off as an online joke, so much so that musicians and artists of the movement later sought to eschew associations with it. After 2013, vaporwave continued growing, but outside of the mainstream spotlight, and spawned endless subvariants like Simpsonwave, synthwave, and mallsoft via Reddit and Tumblr.

Perhaps the most famous work from the vaporwave movement is the Macintosh Plus (Vektroid) album, Floral Shoppe (2011). Both for its music and its album art, because, again, this is a sonic genre as much as an aesthetic one. The album art includes the pre-9/11 New York City skyline, a marble Helios staring blankly, checkered tile reminiscent of a dead mall food court, and a colour palette of turquoise and pastel pink — the iconic duo that was inseparable from ‘80s and early ‘90s fashion. The music? In a retrospective, Miles Bowe described the album as “cheesy saxophones melted into ooze, easy listening skipped and tripped over itself like a buffering YouTube video, and vaguely human voices were slowed into breathy, bland moans” and “it [sounds] like the musical equivalent of a computer virus.”1 The music of Floral Shoppe and the genre it came to define is something we’ve all heard before. Not necessarily in the exact configuration found in a vapor track, but its tunes no doubt bring to mind the chimes of elevators, workout tapes, and hotel lobbies from eras bygone. Vaporwave samples consumerist beats, the stuff meant to fade into the background while we consume or become consumed, at work and the mall, and appropriates them into a nostalgic drowse. Another vapor act, 18 Carat Affair, took 1.5 seconds of a Spyro Gyra song from the ‘80s, stretching it out and tormenting listeners with its dreaminess while producing something new in the process. Personally, I never felt like vaporwave was ‘80s music (as it’s often simplified to be defined as), but rather a representation of an idea of the ‘80s, by plucking very specific snippets and exaggerating them to fulfill that idea, regardless of how true to reality the idea is.

Schizophrenia

Vaporwave’s imbued with a strong sense of sadness, too, while it lives off of being lifeless. Take the word vaporwave riffs off of — vaporware, which is software that never sees the light of day, forever being relegated to the ether. Foundationally vaporwave isn’t meant to be real. In fact, it emphasizes its dreaminess to produce a foreboding melancholy. Despite having a beat, vaporwave’s music is, at the end of the day, empty, much like how those of us drawn to this artistic movement feel. There’s a hollowness even when there’s a beat.2

Vaporwave’s caught between being alive and dead, which mirrors nostalgia and memory more generally. Its content looks to periods that are no longer alive because they aren’t the present but keeps them alive as fragmented floppy disks full of corrupted memories and ideas of the past. Through this, vaporwave and its million subgenres are a purgatory “devoid of time and space.”3

But, lacking a sense of time and place is also the postmodernist condition. It’s an inherently ahistorical and atomizing social ordering, something that cultural theorists call “schizophrenic.”4 Jaime Roberts explains what this means pretty well. For them, schizophrenia is the breakdown of meaning. Postmodernism is decentralizing and is therefore unable to organize itself coherently with a real sense of meaning. Regarding time itself, postmodernism scrambles past, present, and future, rendering it incoherent. Therefore, “postmodernism is schizophrenic knowledge.”

This is also where postmodernism being the end of history comes from. The concept, coined by Francis Fukuyama in the early ‘90s after the fall of the Soviet Union, argues that our current sociopolitical ordering — neoliberal capitalist democracy — is the last iteration of human governance. Thus, liberal democracy “won,” transcended modernism, and became postmodern. While historical events may still happen, those events will occur within the same specific version of society. It argues there is nothing more. Instead of pharmacare and gender equality, we got John Hughes on video cassette. And despite a growing list of complaints since neoliberalism popped up (in tandem with postmodernism) in the ‘70s, it’s still the only way, permeating all but a few black sheep nation-states. Liberal democracy continues to persevere, by gobbling up its complaints and spitting out ersatz reforms, only proving Fukuyama right. This is what allows postmodernism to scramble history to become schizophrenic. Our sense of place within history and grasp on a lineage to time has been corrupted. There is no more struggle for tomorrow, because we’ve culturally imbibed the idea that today is our tomorrow, and this is all there is, so all we can foresee are milquetoast amendments to the current order.

By contrast, modernism was progressive and rooted in a sense of time and place. It was revolutionary in a way that postmodernism isn’t. Surrealism, Dadaism, Communism, the Welfare State, Suffrage, Bauhaus, the Space Age — modernist renditions of a new world, shattering the previous ways that, in many cases, had been the ways since time immemorial. Postmodernism is reactionary, a return to old forms. It dissolves progress and instead ruminates in itself. Even the gaudy post-modernist architecture and design I adore is an attempt at reconciling the past with modernism. It seeks classicalism and populism and marries them to contemporary technological capabilities, made possible by the same laissez-faire capitalism its philosophy extolls.

So what happens when modernism’s experiments (such as socialism) are over? Liberal democracy becomes humanity’s final form, where time and place no longer matter. And the implications of that? Culture melts and becomes self-referential, rootless, ironic, and nostalgic, untethered from anything specific and free to be nebulous.5 Postmodernist technology has allowed us to access anytime, anywhere with increased ease that further corrupts time and place. Altogether, eventually, there’s no longer a distinct look or feel to a period of history because anything could be in now. Time becomes meaningless.

If you’re still a bit lost in the sauce of postmodernist schizophrenia (as I was when I first learnt about this), maybe it’s easier to explain with examples of how culture has changed over the past 50-60 years. Within the Western world, the modernist era of the early-mid 20th century was characterized by a broad monoculture. While not everyone was the same, there was stronger conformity and a more rigid set of ideals. Media consumption was largely confined to what was going on at the time — you couldn’t just access music from 70 years prior in 1936. Even in print, magazines focused more on general interest, such as the iconic Life Magazine. This meant everybody consuming the same stuff at the same time. Think about how everybody used to tune into the same radio shows, then television shows, and talk about them collectively at the water cooler the next day.

By the shift into postmodernism, in the ‘70s and ‘80s, this monoculture saw its first cracks. Special interest magazines, cable TV networks with specific programming, the popularization of various subcultures via that niche media circulation, and so on. There was also an early revolution in media accessibility. With VHS and cassette tapes (and vinyl a bit earlier), you had a relatively portable medium through which you could watch any movie or listen to any album from any time at your leisure. You weren’t tied to whatever the theatre, TV station, or radio decided to air. By the ‘90s, there was of course the World Wide Web and the rise of home computing, which allowed niche communities to flourish, which was good, but also eroded the monoculture even further. This laid the foundation for media and culture to become even more accessible, out of time and place, as the Internet allowed people from disparate geographies to connect, irrespective of the mainstream culture, and reference the past, present, and future with ease, no matter the year.

‘90s cinema started echoing postmodernist values in its cultural criticism, something that only heightened after the millennium and now Hollywood can’t stop dredging up old franchises. At least in the ‘90s, it was fresh. Scream (1996) is a great example of the ‘90s-style self-aware irony that pokes holes at the tropes of what came before, getting off on the subversion of expectation. In the 2000s and early 2010s, shows like Community and Modern Family exaggerated what was happening in the ‘90s by being ultra-meta, always in on the joke, and regularizing nostalgia. This was also the time of hipsters and their endless references and gimmicky nods to the past.

And of course, globalization was happening in the background, too, further eroding distinct cultures by allowing the spread of Western capitalistic ideals across the globe at breakneck speed, transmitted by the soft power of digital technology. It’s why people in Atlanta don’t have Southern accents anymore and why a vegan restaurant in Seoul looks like a vegan restaurant in Toronto. For as much as postmodernism has destroyed the monoculture, it’s also ironically created a generic new one through globalization. We may have more variety, but it’s the same variety as everywhere else, in virtual lockstep, thus rendering it untethered from a sense of time or place. It’s whenever, wherever, everywhere, everytime.

The dissolution of the old monoculture rooted in time and place and the entrenchment of a new atomized monoculture of nowhere and everywhere didn’t happen overnight, though. The ‘80s and ‘90s, the most referenced period in vaporwave art, still had a distinct look and feel and appear as a specific period in history as a result. The scrambling of the monoculture had begun, but not enough to destroy a common sense of culture. Even the 2000s still have a faint sense of belonging to a specific period. It’s only been in the past 10 years that I’d say that postmodern schizophrenia had finally succeeded in defeating most traces of rootedness viz time and place. This is largely due to social media’s growth since the late 2000s, alongside other media apps like Spotify, which have reduced the friction of someone accessing any time period to a bare minimum. Instagram and TikTok have allowed for multiple fashion revivals to happen at once, cemented by the strength of online microcommunities. Depending on your niche, anywhere between the 1920s and 2000s could be in vogue right now, in a way previously inconceivable. While there are still trendy things (specifically late ‘90s/early 2000s fashion), if you honestly had a well-executed ‘50s suit or ‘80s rave fit, you’d be just as fashionable, rendering these words meaningless.

You see this with popstars too, who will go from ‘80s metal to ‘70s disco to ‘00s bubblegum and back to ‘60s folk rock without missing a beat. With monoculture out of the way, you have artists like Billie Eilish, whose influences range from Lana del Rey to Green Day to Justin Bieber to Damon Albarn to the Beatles. Her ability to easily access a litany of distinct artists, from different time periods, out of chronology, to be artistically influenced by, is only possible en masse through the Internet. Before, you were limited to what was of “your time” unless you listened to the oldies AM station or your parents had good taste (which would’ve similarly been limited to what was of “their time”). Being plucked out of time has also allowed artists like Kate Bush to have their decades-old songs re-chart thanks to postmodernism’s schizophrenia-inducing technology. Streaming services like Netflix are a reflection of ahistorical values, with its broad range of offerings appealing to a large range of niches and titles spanning different decades, all easily accessible with the click of a button. Thanks to a Stranger Things refresh on Netflix, Bush’s 1985 single was able to memetically find new life on TikTok, where it was heavily sampled in short videos, completely removed from its original context, but pushing it back onto the charts.

But this obsession with the past has come at the detriment of anything truly new, in fashion and beyond. It’s part of the entrenchment of neoliberalism, the dissolving of alternatives to it, and thus, proving Fukuyama right. If this is all there is and there’s nothing left, it’s no wonder we’re left to cycle through a highlight reel of actual history, when there was progression and innovation. This process also makes us yearn for previous eons and reinforces the artificiality of the present. Our contemporary world is a land of pastiches of the past, the only alternative is the blank void of greige that somehow every landlord thinks is desirable.

Nostalgia’s emblematic of the dark side of the dissolution of monoculture. Think about how the era of “must-see TV” died with Game of Thrones. Now what are people supposed to talk about with co-workers they don’t like? Jokes aside, atomization creates less cohesion and disrupts the potential for camaraderie. The plethora of options afforded to us by streaming services seems nice until you think about how all that’s gotten us is a splintering of options and left us overwhelmed with mediocre Netflix shows. Instead of everybody talking about the same “must-see” show, your co-workers are recommending endless shows that you say you’ve “been meaning to get to” but never will because we’re drowning in options and thus, ironically, this ultra-connectivity disrupts genuine connection. This is all very sad and disheartening, which is how we get things like vaporwave, an inherently nostalgic and melancholic genre.

Nostalgiabait

As a product of Millennial artistry, vaporwave points its lens at the pre-9/11 childhoods of my generation: the ‘80s and ‘90s. This period was when postmodernism, which began in the ‘70s, really hit its stride and became the dominant ordering of the Western world. The brass and terrazzo I adore are part of this, but it’s interwoven within a broader sociopolitical project of late capitalism and neoliberal supremacy. Vaporwave’s obsession with late 20th-century cultural artifacts and technology is interwoven within this too.

In the late 20th century, we saw the exceptional rise of digital technology. Video games, personal computers, mobile phones, digicams, computer-generated imagery, the Internet, compact discs, MP3 players, and pocket calculators. This tech is the fodder for vaporwave nostalgia. The ‘90s were highly referential towards itself and the impending millennium. In hindsight, it seemed like the last time the zeitgeist had optimism. But it also felt like it was at the end of something, uncertain of what was to come. And the decades since have not only become less optimistic but unrooted within a place in time. We’re not beating the end of history allegations today, I fear.

Nostalgia is a prominent fixture of postmodernity. While some form of melancholic wistfulness towards the past has probably always existed, the last half-century’s ideology has allowed it to blossom into gargantuan proportions. The easy ability to reference the past thanks to the Internet helped us move beyond monoculture, but it’s also more deeply entrenched a collective nostalgia, even for times we never experienced. And just like monoculture’s dissolution took decades, so too did nostalgia’s stranglehold on culture.

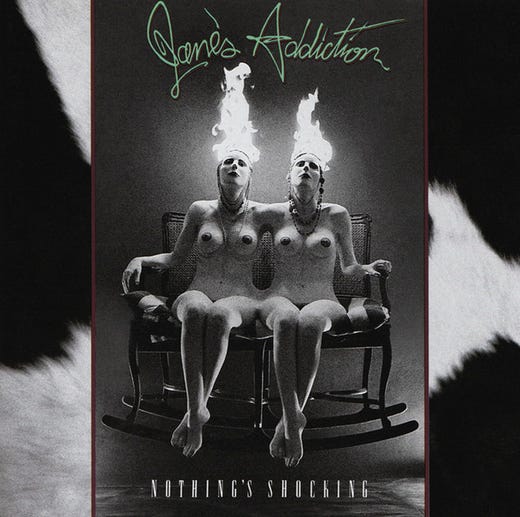

In 1988, Jane’s Addiction released their album Nothing’s Shocking, and they were so right for saying that. It spoke to an early sense that perhaps the neoliberal world was all that’s left, with nothing to surprise us. By 1995, Thom Yorke waxed on about how he “[wished] it was the ‘60s, [he wished] that something would happen.” This begs the question: is postmodernity akin to getting the bends? The Internet has desensitized us to so much while, culturally, nothing new appears on the horizon. You can listen to Detroit techno from the ‘80s and, sound production aside, it doesn't sound that different from contemporary techno. Rock is in even worse shape, seemingly immune to innovation since the death of Kurt Cobain (and arguably before that). According to Alican Koc, late capitalism pushes us away from history as much as it draws us to seek it out. We are increasingly seeking out “blank parodies,” pastiches of a simulated past that may or may not have existed as a reflection of our rootless reality.6

Hollywood’s a great example of this, a cultural machine that many agree is “out of ideas,” content to turn everything into franchises and never letting stories end in order to milk our nostalgia for profit. Franchises (and remakes) are the only things that stick out about post-Iron Man cinema as a broad cultural stroke, which themselves are rooting for another time to fill our rootless present. Even the lauded film of the summer, Barbie, written about as a break from this endless cycle, is not a children’s movie so much as an attempt to coddle Millennials and Gen Z with neoliberal propaganda drenched in the warm embrace of nostalgia. The Dark Knight helped launch endless DC and Marvel movies by showing Hollywood a “proof of concept” with an artful, thought-provoking piece of film. Mattel similarly has its own plans for milking its IP by creating a new cinematic universe. Lena Dunham has dibs on Polly Pocket, apparently.

The perception that American film is unoriginal and all that gets made are hypercommercial spectacles of little substance isn’t new, either. Writing in 2011, Mark Harris noted that films such as Top Gun are “pure product—stitched-together amalgams of amphetamine action beats, star casting, music videos, and a diamond-hard laminate of technological adrenaline all designed to distract you from their lack of internal coherence, narrative credibility, or recognizable human qualities; they were rails of celluloid cocaine with only one goal: the transient heightening of sensation.” Neoliberalism has given rise to corporate monopolies, Hollywood included, such that we are in a New Studio System of the same mega-conglomerates gobbling up the vast majority of space at your local multiplex. On top of that, in times of upheaval, the studios, that have slowly absorbed all dissent, become risk-adverse as audiences are unwilling to fill theatre seats. Be it Blockbuster and Netflix removing the need to go to the theatre or economic crises like 2008 and covid, the introduction of these shifts follows the decline of artful films that move us. The focus is on spectacle to get people back to the theatre or by franchising out and building IP into its own empire such that films are only a two-hour commercial selling action figures and clothes. And in the past 20 years, a lot has upended Hollywood, while power has consolidated, such that most of the top-grossing films in North America today are franchises, remakes, or reboots.7 Auteurs like Scorsese have lamented this shift as the end of cinema altogether, as they came from the modernist tradition of art being able to transcend capital. But postmodernism “integrates art into capital,” as film critic Frederic Jameson argues.8 This is merely the world our governing ideology creates.

The framework for the endless drudgery of current cinema goes back to the early postmodern period of the ‘70s and ‘80s. While a new generation of filmmakers rose from the ashes of the Hays Code in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, one that opted to show more human, introspective, and thought-provoking ideas, they eventually led to the creation of the blockbuster. Broey Deschanel notes that Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) showed the commercial viability of these sorts of films, and instead of having movies run throughout the year in theatre off of word of mouth, studios invested more into marketing and raising the importance of opening weekend sales.9 By the ‘80s, this framework was kicking into high gear, with the popularization of sequels like Back to the Future and increasingly utilizing film (and television) as vessels to sell branded merchandise. Why? Because, with the rise of home video, the film itself wasn’t enough to keep people coming to the theatre.

Vaporwave engages with this media ordering, too. While it may be endlessly nostalgic for the end of history and is an attempt to feel the last gasps of history, there’s often a darkness to its visual language. You may see nods to early video games, old cartoons, and nascent digital technology in vaporwave art, but their inclusion isn’t entirely admiration. Those children’s shows of the late 20th century that so many remember fondly were clever commercials that got kids nagging their parents for toys and other themed gadgets, continuing the cycle of consumption. What’s Transformers without your own personal Optimus Prime to battle your own personal Megatron? By citing it and many other cultural emblems of the pre-9/11 postmodernity, vaporwave is taking back what this period eroded: our individuality and creativity, while calling into question our consumptive habits.

Vaporwave isn’t all negative, though. What I’m saying is that vaporwave’s relationship towards early postmodernism carries nuance, and can (particularly in aggregate) be read both ways. There’s still a lot of legitimately nostalgic elements in vapor art. Early postmodernism had the scrambles and shifts towards atomization, but before it matured into the rootless present. The heavy citation of cassettes, the Sony Playstation, and Windows 95 seem to index the “final moment of departure into the hyperreality of the late-capitalist moment for millennial creators of vaporwave art.”10 For artists, it was also the period of their (and my) childhood, when there was still optimism about digital tech. The “Y2K aesthetic” of iridescence and translucent plastic gadgets, most popular from 1997 to 2001, highlights this well, envisioning a fun and exciting techno-utopia for the new millennium. But 9/11 quickly soured expectations and fashion went towards chunky Americana while technology started looking like it wants to kill you.11 Instead of the Information Superhighway, we got Donald Trump as president, but vaporwave calls upon an early innocence to postmodernism’s effects.

Through this, it could be said that vaporwave is a nostalgia for a future unrealized. It’s borne out of the hopeful hauntological implications arising from the rapid onset of digital technology in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Or at least the hopefulness we remember them having, because there were many cyberpunk critiques of this rising technological wave in the ‘80s.12 And even though vaporwave is trying to reconnect with history by contacting early postmodern objects, it’s still a mashup of disparate elements, appropriated from their history and placed in a new context, just like any other postmodern nostalgia. Vaporwave wants to touch history but the very act of reconciliation is only unravelling history further, causing the same alienation that made us seek out this brand of nostalgia in the first place. For Koc, vaporwave is mapping the nostalgic effects of postmodernism’s “schizophrenic haze.”13 There’s an impossibility inherent to vaporwave. It doesn’t imagine the ‘80s as it was, but picks snippets and exaggerates them into a feverish fantasy built on semi-opaque recollections. But I think vaporwave’s kind of in on the joke. Its creators often incorporate absurd and deliberately unreal subject matter, like the penchant for hypnotic endless sunsets to contrast the stretches of purple neon nightmares going on ad infinitum. It’s looking at Golden Girls through the lens of RoboCop.

David’s intermission

One of the more curious cliches of vapor art is the high dosage of Greco-Roman motifs, particularly classical columns and statues of David. To be fair, these references existed in postmodern design and decor in the period that vaporwave heavily cites. But there’s something more to it.

Images of marble Davids are also a commentary on Western idealism. David’s appropriation into the present, in vaporwave and elsewhere, reflects a nostalgia for the halcyon days of Western civilization and a desire to rekindle our past. The statue itself, by Michelangelo, was created in early Renaissance Europe, as part of a desire to reach past highlights. And by synthesizing Christian mythology with Roman aesthetics (particularly Hercules), a masterpiece was born. Clearly, the West has a penchant for nostalgia. An ex of mine used to say that neoclassical architecture is inherently imperialistic and fascistic. And when you look at the grand nation-building that America and Germany did with Greco-Roman motifs, attempting to touch history then as vaporwave does now, it’s not that wild of a thought. Both the US and Germany saw themselves as the New Rome, inspired by Roman militarism and Greek cultural output. The fondness these ancient cultures hold for those of us in the West is because they’re reflexively viewed warmly, ideally, as the genesis of our civilization.

David isn’t only a reference to the West’s origins at large, but also our beauty standards, due to how Michelangelo allowed Roman aesthetics to reverberate into the Middle Ages. If David’s physique is the immortal pinnacle of Western beauty, then his repeated reference in vaporwave is perhaps a commentary on that. He represents an aesthetic ideal but there’s nothing beyond his physique. David stares blankly at us for eternity, perpetually empty, giving us no answers no matter how much we ask him. Thus, he exemplifies the hollowness of chasing beauty standards. David’s shallowness infused with digital cultural emblems in vaporwave also calls to question our uniquely postmodern beauty standards. In the Internet age, we’re bombarded with endless neo-David’s, perfect physiques on social media that have intense influence over our thoughts. Thus, David’s inclusion in vaporwave imagery critiques the vapidity of online beauty standards and the harms of chasing them. They’re as fruitless as yearning for some idealized Western beginning and its enduring aesthetic standards.

Within the contemporary picture, Greco-Roman motifs contrast an increasingly dystopian Westernized globe. The influence of Western culture has never been greater, nor has its military might, and yet, we long for the past. In a world where nothing new is under the sun, where rising inequalities show the barefaced lies of neoliberalism, it can feel as though the West is in decline, particularly when you look at its American superpower. Greece and Rome point to an imagined past of an idealized West, not one of rot and rootlessness.

Even post-modernist architecture from the ‘70s to ‘90s recalls classicalism. It still draws on modernism’s disdain for the human scale and love of techno-monumentalism, but vulgarizes it with ornamentation, subverting its function-over-form principles. Corinthian columns painted teal jutting out of steel construction. That sort of thing. Vaporwave is just another post-modernist creation referencing Greco-Roman forms.

The elevator pitch

Muzak, or elevator music, the brand of background music associated with old malls and office parks, is the greatest sonic influence on vaporwave music. Often slowed, mashed up against other sounds, with a cacophony of contemporary concern echoing through the reverb. Its appropriative retromania is distinctly postmodern, with a level of sampling that’s reminiscent of the ‘80s. Paul’s Boutique (1989) couldn’t be made today because the music industry caught up and started demanding royalties for samples, thus corporatizing the art of the sample. But vaporwave resists corporatization by appropriating corporate music.

Elevator music, the essential fruit of vaporwave, is some of the most neutral-sounding music humans have created. It’s perfectly pleasant in a benign way. And while this may seem harmless, Muzak was deliberately employed in elevators, retail concourses, and cubicles to allow corporations to capitalize on people by numbing them into comfort in otherwise soulless, non-places like malls and offices.14 Its pleasantries keep people consuming and working and allows the churn of capitalism to see another day.

It’s ironic and subversive to see vaporwave take this corporate, sanitized music, and use it for something new, and for free on the Internet. Muzak, emblematic of a loss of control over our lives as we submit to the machine, was seized and turned into public property. As artists and as consumers of art, vaporwave allows people to regain some agency by taking back from the thing that stole so much. And that, to me, rocks.

This cultural criticism goes beyond sampling and stretching retro mall music, however. Vaporwave loves to cite ‘80s and ‘90s pop culture and technology and Windows 95, the Gameboy, children’s cartoons, and Deloreans are just as much a part of this critique as ‘70s and ‘80s chimes. Regarding popular technology, vaporwave engages with them by contrasting them with today, when many of these tech firms have blossomed into something out of a cyberpunk hell. It’s showing us that Blade Runner was right all along. So-called big tech wasn’t called big tech back in the 20th century, and there was generally more naivete around new technology. Now people are sick, which is why the Apple Vision Pro and many other new gadgets designed to keep us engaged online are being met with way more disdain than the N64 ever got. But there were hints that cyberpunk authors and other critics noted early on. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have schlocky horror like Chopping Mall.

The ‘80s were the start of this techno-dystopia and by heavily citing it and the ‘90s, vaporwave confronts our rosey nostalgia for this time and drenches it in dread and alienation. This melancholy comes from the present, but our path to this reality started in the early postmodern period. That being said, vaporwave’s nostalgia for this era is immense, and it’s not always critically calling it out for the dystopia it birthed. Vapor art yearns for an unrealized future. A world of immense consumer growth, when kids were told they could be anything they wanted to be, before 9/11, before the 2008 crash, and before covid. It seeks to imagine a world in which the techno-optimism of the ‘80s and ‘90s never stopped, and its promises did self-actualize. Despite becoming the last of history, there was still a(n increasingly fraught) relation to history and was the last period where things felt inventive rather than pastiche. There’s little excitement towards the future in the popular imagination because the world that postmodernism turned into ended up being kind of a killjoy. It’s also important to realize that the period vaporwave is so nostalgic for wasn’t always so great, and its impression on vapor artists is tainted by their hazy childhood memories or in some cases, a completely synthetic nostalgia. But within the Millennial POV, it’s a cozy recluse from the nightmares of now.

Final thoughts

Vaporwave is the art of alienation while its art also alienates us. It’s reflective of our rootless age, wherein we’ve been fed neoliberal dreams that haven’t panned out but also haven’t upended the ideology’s supremacy. Marx suggested that the further workers get from the means of production, the more alienated they become. Today workers aren’t just one piece of the puzzle making a product that is claimed by someone (or something) else, they’re completely obfuscated from the means of production as the main jobs in the Global North are in the retail and services sector, with the greatest abstraction of all, finance, underpinning it all.15 The jingles that vaporwave apes is the music of this atomization and their reference is an attempt to regain control and reflect on that alienation.

Ironically, I’m writing this despite never being that into vaporwave music when I was younger. I appreciated its nostalgia, but it always felt a bit too chill for my tastes. Aside from Blank Banshee 0 (2012) and the synthwave subgenre (which legitimately slaps), its music never appealed much to me — pure vaporwave always felt a bit sleepy. I was drawn more to the ideology and, to a lesser extent, the aesthetic behind vaporwave than the music that created it. I’ve felt a kinship with vapor artists in our shared nostalgia.

My cultural affinities, from media to design to fashion, heavily romanticize the same ‘80s and ‘90s that vaporwave does. Even though there are other eras I’m interested in, the ‘80s and ‘90s take up the bulk of my wistfulness, regardless of how well I actually remember them. Gen Z taking fashion advice from my middle school years feels like a hate crime by comparison. We’re so removed from the 20th century that I’ve witnessed the collective transition from nostalgia for pre-Internet days to pre-social media days, from film cameras to “digicams.” But when I was younger, art and culture were more like vaporwave, with the collective nostalgic haze pointed at the ‘80s and ‘90s more than the 2000s. And that still pervades me because there’s nothing in 2006 worth getting teary-eyed over. That was a time of a lot of homophobia and fatphobia for me. But the ‘90s I was just young enough to have an idealized memory of and the ‘80s are something I grew up with from the afterglow of those around me and lingering cultural artifacts, and so both have a warm place in my heart. They’re a cozy recent past to enjoy, when there was more optimism and a greater sense of time and place, before the Internet destroyed us and when our main, everyday tangible pieces of culture weren’t just dystopian electric black voids of varying sizes.

This nostalgia is why I now have a penchant for the PoMo design of the ‘80s. It’s why a decade ago I was obsessed with ‘80s alternative and ‘90s indie and refused to listen to anything released after 2000. It’s why I long for tangible media… photo albums, Blu-Rays, and cassettes, in a world where everything lives in atomizing gadgets. I’m addicted to the idea that the past provides me, much like vaporwave does for its creators and viewers, and it pervades my life in so many ways, particularly in my tastes and creative inspiration. Because, despite its faults, the late 20th century is authentic, not rootless and dystopian.

Compared to today, the ‘80s and ‘90s feel genuine. People aren’t earnest anymore because to be earnest is to be cheesy, and there’s nothing worse on the Internet than giving people the ammunition of your deepest thoughts to be used against you. More superficially, Memphis is interesting in a way that greige isn’t; The Matrix is cool in a way that the MCU isn’t. Contemporary cinema is alienating. We spent so long chasing clearer and clearer image quality that now we’re in 4K UHD and things look more real than real. We’ve come out the other end and our pursuit of ultra-realism has ironically alienated us from things that look real. In order to regain a thin veneer of authenticity, creators of crisp digital images sometimes add the very things we were previously trying to get away from in post: analogue imperfections. VHS static, film grain, shifty movements, and other aspects of prior technical limitations. All of this is why I have an appreciation for the technical peak of celluloid in the ‘90s and 2000s. Those movies feel more real and that’s cool.

Still, looking back over vaporwave music and art for this essay gave me another kind of nostalgia, not for the late 20th century, but for the early-mid 2010s of my young adulthood. I recognize my generation's youth in Azealia's “Atlantis” video and the ever-growing gulf of time between then and now. So I'm nostalgic for something from young adulthood that's nostalgic for my early childhood and the time immediately before my birth.

I also can’t help but notice vaporwave in other art. If you’re homosexual or just European, one of the songs of the summer has been Kylie Minogue’s single “Padam Padam.” It may not sound like it, but the tune takes on many vaporwave sensibilities. Its main synth beat is retro-infused and melancholic-seeming, while Kylie herself sings about sex with the most vacant stare. Like she’s been so commodified by the industry and there’s an army of gays playing her like a marionette. Her wardrobe in the music video subtly recalls “Oops I Did It Again” as much as her synth evokes an ‘80s-esque HAL-9000. The nostalgia doesn’t end there — the props of Padam’s music video include mid-century diners, signs, and televisions. Kylie’s song and video seems like it’s putting the 20th century in the blender and seeing what sticks. And so it feels out of time, in mourning almost, even while the background dancers do their thing. “Padam” doesn’t look vaporwave, but feels it. Maybe vaporwave has transcended itself. Kylie’s newer video, “Tension” feels aesthetically pulled from Blade Runner 2049 in parts, far more blunt than “Padam” is.

Now we aren’t just dealing with post-history, but with social media and AI, we’re looking at a post-truth world. The real and tangible, if trends remain, will continue to be obfuscated from us, feeding and exaggerating our rootless culture and sense of identity. There are still hints of trends and a sense of place in the 2020s, but it’s a fraction of what existed only 20 years ago, as postmodern culture, entrenched within the Internet and globalization, has continued to fracture time and place. There’s not much left and it doesn’t seem like what’s left will be around much longer. Soon, the ideals of neoliberalism will have been maximized to their fullest extent, and the project’s last phases fully built out. For what it’s worth, I don’t subscribe to the notion that this has to be humanity’s final form, but changing that requires us collectively deciding it isn’t and pushing for a better tomorrow. Otherwise, we’re just going to be stuck idealizing the past, when its positivity and rootedness should be inspiring us to move toward something better. I hope that we get there, even though I’m the most nostalgic person I know.

https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/macintosh-plus-floral-shoppe/

www.youtube.com/watch?v=itqsik7grQM

ibid

https://jaime-roberts.medium.com/schizophrenia-in-postmodernism-ff17e0045b18

https://www.loudandquiet.com/short/all-that-is-solid-melts-into-air-10-years-of-vaporwave/

https://capaciousjournal.com/cms/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/koc-do-you-want-vaporwave.pdf

youtube.com/watch?v=cuGPFq_GI10

ibid.

ibid.

Do You Want Vaporwave by Koc. Pg.71.

credit to my partner for this punchy one-liner

https://capaciousjournal.com/cms/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/koc-do-you-want-vaporwave.pdf

ibid. Pg.70.

youtube.com/watch?v=itqsik7grQM

https://www.loudandquiet.com/short/all-that-is-solid-melts-into-air-10-years-of-vaporwave/