No era in Edmonton’s history is as iconic as the 1980s. For me, Edmonton is an ‘80s city, and I don’t mean that pejoratively. Think about it — it was the time of Wayne Gretzky’s dynastic stranglehold on the Stanley Cup, when the original megamall — West Edmonton Mall — was built, and when River City became known as something a bit more distinct: the “City of Champions.” It was one of the most culturally significant times in my hometown’s history, an intoxicatingly legendary period. I’ve long perceived it as a time of big thinking and bold visions for Edmonton, feverishly transcribed onto zany post-modernist aesthetics. Because of these big moments, particularly in sharp juxtaposition to my upbringing through the sleepier ‘90s and 2000s, it almost feels like this was Edmonton’s pinnacle.

But it wasn’t. The truth is, the ‘80s had some big splashes, but for a lot of Edmontonians and Albertans, it was a difficult time due to the state of the economy, which spawned two recessions, mass foreclosures, and heavy job losses. If anything, the ‘80s were a transition period between the oil-fueled party of the mid-century and the stagnant austerity-addled era I grew up in. While it wasn’t unequivocally the darkest time in Edmonton’s post-war history, it was in many ways the era that planted the seeds which grew into the city’s ‘90s nadir.

So where did this fever dream of Edmonton in the ‘80s come from, if things were so bad? Obviously, it didn’t sprout out of thin air. But I came after that period had closed, when it was just a recent collective memory hanging over Edmonton, so my idea of the ‘80s was always going to be divorced from reality to some extent. Coming after the oil glut and controversial National Energy Program (NEP), all I saw was the cultural legacy of Black Friday and a preponderance of ludicrously brassy interior design. For sports fanatics, of which there are many in Edmonton, the ‘80s were a kind of ‘glory days’ for the city’s two major sports teams: the Oilers and the Eskimos, one that people were quick to reminisce on fondly when I was growing up. The two teams were consistently the champions of their respective leagues throughout the 1980s and Gretzky remains one of hockey’s most legendary players. In a time as stagnant for Edmonton as my childhood was, it’s not surprising many romanticized those times when the city embodied the “City of Champions” moniker most obviously.

I still remember feeling left out on the reference when I was a kid and people would wax poetically about Gretzky because almost everybody around me was old enough to remember this then-recent period. Even if I wanted to watch old sports highlights (I didn’t), I wouldn’t be able to get what I wanted: to know what it felt like to have been there. And that’s the crux of it: there’s this aura that the ‘80s exudes for me, imprinted from an early age. People back in the early 2000s were doing the same thing I continued doing into adulthood: projecting an idea of the past onto a place by cherrypicking a highlight reel to fit the narrative. And I was doing it for the same reasons: Edmonton in the ‘90s and ‘00s had lost its groove and felt down in the doldrums, especially compared to ascendant rival Calgary. By the time things began changing in the early-to-mid 2010s, my idea of Edmonton was so firmly ingrained in a particular iteration of the city that the changes were alienating. I like my Edmonton stuck in the ‘80s, the way it was when I was little, faults and all, and don’t like the emblems of that period being jettisoned.

What I hope to interrogate here is the root of this nostalgia I have for a time that never existed in my memories, only in my dreams. But also, why, from the outside looking in, Edmonton in the ‘80s was and remains so fascinating. I want to shatter the illusion as much as elevate it as I take you to the belly of the beast that is the fever dream of my nostalgia. In doing so, we’ll look at how flawed our perceptions of the past are, despite how much influence they have in maintaining our ideas of history.

The Party

Before getting into the ‘80s, it’s worth noting the epoch that came before and helped create it. The era from roughly 1947 to 1981 was an utterly transformative one for Edmonton, with huge growth and big thinking, all largely due to a new economy based around petroleum. Back in the 1940s, Alberta had a population similar to Saskatchewan’s, compared to today, where the province has quadruple the population of its eastern neighbour. The presence of oil was already known to First Nations for a long time and early discoveries in the 1910s at Turner Valley (southwest of Calgary) produced Alberta’s first oil boom. Settlers knew that the province’s geology shares the same sedimentary basin with that of the established oil-producing areas of Texas and Oklahoma and altogether this led to speculation and exploration by North America’s oil companies, particularly as Turner Valley’s oil was running low by the 1940s after peaking in 1942.12 Imperial Oil alone dug 133 dry holes in a row3 until it struck black gold in February 1947, just outside Edmonton at Leduc No. 1, forever changing Alberta’s economy. This was the start of Alberta’s protracted mid-20th century oil boom. As more sites were found, growth accelerated for more than a generation.

By the 1970s, the global economy was changing. Although the 1950s and ‘60s brought a lot of economic growth to many cities throughout the continent, that would change by the ‘70s as the optimism of the previous decades turned pessimistic. But this wasn’t universal — amid the energy crises of the decade, Alberta continued chugging along, benefiting from a new expensiveness and artificial scarcity of oil. The cost of oil soared initially due to the Middle Eastern Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) embargo of 1973, limiting exports of petrol to countries like Canada and the United States, spawning a crisis in 1973 of fuel shortages and increased prices. The embargo against Western nations was due to American support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, whose funding and armament allowed Israel to win against Arab states. The war was triggered by Syria and Egypt as a retaliation against Israel, who, in the Six Day War of the 1960s, captured significant territory in Egypt, Syria, and Jordan, who were backed by OPEC. By 1979, the Iranian Revolution caused a drop in exports as Iran was one of the main oil exporters at the time, which pushed prices upwards, and created a second oil crisis. Oil peaked in 1979 at $40 per barrel due to instability in the Middle East, whose oil had been supplying much of the world at the time.4 This opened a window for Alberta to get even richer off of its vast oil reserves by selling to places reeling from the embargo, such as the United States. While this was still the era of conventional oil, Alberta would start shifting attention towards the vast oil sands near Fort McMurray in the '60s and '70s, one of the largest oil reserves in the world.

In the ‘60s, Great Canadian Oil Sands, formed by Sunoco (which lives on in Canada today as Suncor), built the first large scale oil sands mine, which became operational by 1967,5 just ahead of the ‘70s oil crises. Being that the oil sands are more expensive and difficult to refine and turn into industrial products as compared with conventional oil, the heightened cost of oil in the ‘70s made it more financially beneficial to exploit the oil sands. In fact, by 1978, Syncrude opened the second mine in the Athabasca oil sands with the help of government funding.6

While global politics no doubt spearheaded this “modern day gold rush,”7 local politics fostered it too. In 1971, the Progressive Conservatives (PCs) were elected under premier Peter Lougheed, which was the start of a new political dynasty for Alberta that lasted until 2015. The PCs were quick to aid in the development of the oil industry,8 and by 1973, when the first oil crisis occurred due to the embargo, Alberta’s oil industry was sent soaring, producing a “superheated economy” that took hold of Edmonton.9 Lougheed's government would continue incentivizing oil exploration, which had the effect of "pouring gasoline on a fire."10 It became so easy to get rich in Alberta that young people, with only a few years experience under their belt, would get together in small groups and found oil companies and find success that way.11 As Tingley notes, these conditions drove thousands to come to Edmonton seeking the prosperity that the oil boom provided, likely in contrast to the deindustrialization and decay happening elsewhere. 26 high-rises were built just in Downtown Edmonton, while 3 major malls were completed, the Citadel Theatre opened, and it seemed like everything was on the move in the city.12 Beyond Edmonton, the province’s population grew by a third over the ‘70s and Calgary issued more than $1 billion worth of construction permits annually.13

As much as I’ve conjured up this idea of the ‘80s being a fever dream, if any era in Edmonton’s history was feverish, it was surely the ‘70s. This period was the culmination of a 30 year long boom and, with the growth stalled elsewhere, Alberta found itself in a special position as a land of opportunity. The epoch between Leduc and the NEP was a prolonged party in Edmonton that reached its most daring moments in the ‘70s. It was this decade that Edmonton went bold and innovative in ways it hadn’t before as the boom instilled an ego in the city that provoked a new sense of grandeur.

In 1972, Edmonton was chosen to host the ‘78 Commonwealth Games, which was the first big international sporting event in Alberta’s history.14 That same year, the Oilers debuted as part of the World Hockey Association (WHA) before joining the National Hockey League (NHL) in 1979. The Coliseum that replaced the old arena, Edmonton Gardens, opened in 1974, providing a new home for professional hockey in the city. Meanwhile, Edmonton’s other major sports team, the Canadian Football League's (CFL) Eskimos, began a streak of Grey Cup wins in 1978, the same year that the team moved from the aging Clarke Stadium to the new Commonwealth Stadium, built for the eponymous games.15

The Commonwealth Games also helped spur one of Edmonton’s most forward-thinking initiatives: building North America’s first modern light rail transit (LRT) system in the ‘70s. The result of revisions to the City of Edmonton General Plan in the early ‘70s.16 This update pursued a new focus in transportation planning based around public transit, a sharp contrast to earlier plans to slice up the city and its ravines for a robust freeway network. Instead, Edmonton deliberately wanted to reduce automobile usage17 while it was ironically getting rich off of the world's addiction to petrol-powered private transport. By the mid-1970s, construction began on Edmonton’s LRT,18 at a time when only Toronto and Montreal had rail-based public transit in Canada. It opened in 1978, just in time for the Commonwealth Games, linking the new stadium and hockey arena with downtown and northeast Edmonton. Rather than be content with following the trends towards automobility that were in vogue at the time, in the ‘70s Edmonton was a trailblazer in devising alternatives to that status quo. Today, light rail is one of the most sought-after infrastructure projects for North American cities, and Edmonton was the archetype. Edmonton was that girl.

Edmonton’s often strange architectural choices are something I associate more with its post-Commonwealth Games vernacular, but you can see the beginnings of it in the ‘70s. While the Edmonton of today has a discernable and peculiar penchant for pyramids, it all started in 1976 with the Muttart Conservatory, popping out of the river valley’s shrubbery not unlike how the Pyramids of Giza pop out of Cairo’s desert edge. That same year, the ultra-saturated Citadel Theatre moved to its current digs overlooking Churchill Square, another camp classic in Edmonton’s architectural lore. These new landmarks, alongside the Commonwealth Games, new sports stadia, skyline expansion, and growth of bombastic suburbs like Mill Woods are emblematic of how cocksure Edmonton became during the oil crises of the ‘70s. With the LRT, the city showed that it wasn’t comfortable just following trends, and so it set them. Edmonton was bold in a way it hadn't been before, and this would continue into the '80s.

The Downturn

After the ‘70s, the decades-long boom came to a screeching halt in the early ‘80s and Alberta ceased to be a land of opportunity. This was the start of an undoubtedly dark time in Edmonton’s history, caused by wider politics and a massive disinvestment from the private sector. The economic conditions of the ‘80s flies in the face of my long-held idea of the ‘80s being some kind of glory days of sorts. My fantasy of what I imagined the ‘80s to be like in Edmonton didn’t come from nowhere, but there’s still a discrepancy between it and what people were going through at the time.

Of course, things didn’t turn grim at the stroke of midnight on January 1st, 1980, and there was still significant development going on in the early ‘80s. The thing is, though, a lot of this was just build up from things that had already started in the late ‘70s or the very beginning of the ‘80s, during the boom, before things went sour. Thus, high-rises rose, the LRT expanded, and West Edmonton Mall (WEM) opened its doors in the early ‘80s, all rooted in pre-recession plans but coming to life during a significant downturn.

A nation-wide recession began in 1981, which was “deeper and and more long-lived in Alberta because of the province’s excessive reliance on oil.”19 The boom-bust cycle reared its ugly head at Wildrose Country due to a big drop in oil prices at the time.20 This was caused by the same external factors that caused Alberta to ride high through the '70s: Middle Eastern geopolitics. Even though Alberta soared through the 1970s, much of the Western world didn't, and the weakened economy and high fuel prices caused a global decline in demand for oil, which lowered prices due to unsold supplies of oil in the Middle East.21 The price of oil peaked in 1980, before declining sharply due to the oil glut.22 For Alberta, as former Edmonton mayor Lawrence Decore stated, "one day the price of land just [dropped], there was no longer people wanting to buy, ... and it was over."23 Bob Lower's documentary Riding the Tornado shows how the bust led to many Albertans losing their jobs, which forced many to sell their homes and draw on lines of credit, but it still wasn't enough — this period saw the highest rates of suicide and spousal abuse in the province's history.24 In 1983, CBC did a segment highlighting the woes of Edmonton's unemployed and how many were turning to phone-in sessions with a radio psychiatrist because their desperation had led them to contemplate ending it all.25 By 1985, the unemployment rate in Edmonton was 15% and 1 in 10 Edmontonians were utilizing the Food Bank, despite social services seeing cuts to funding.26

The other big economic moment of the early ‘80s was the contentious National Energy Program (NEP), introduced by Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government. To this day, the NEP is cited as the reason the Liberal Party is considered dead in the water in Alberta. For Albertans, this program is associated with Western alienation, as it was seen as Ottawa meddling in Alberta’s affairs, and a cause of the economic downturn of the era. The point of the NEP was actually energy self-sufficiency for Canada. Its main goals were to ensure that Canada’s oil and gas supplies were completely domestically produced by 1990, encourage domestic participation in the industry, and to restrict the price of oil so that all Canadians could afford energy.27 It was an obvious reaction to the energy shocks of the ‘70s which may have turned Alberta into Shangri-La but spelled uncertainty for much of the rest of the continent. To this day, despite being a born and bred Albertan, I still don’t quite understand the near-universal contempt for the NEP. I mean, I know why, it’s because Ottawa introduced taxes and price controls, fitting a narrative of Canada unrightfully imposing itself onto Alberta, which ended up cutting into the profits of the oil industry, upon which so many Albertans were getting rich. But it feels incredibly selfish and short-sighted, not unlike debates over transfer payments, despite Alberta being a net recipient of such payments up to the 1960s.28 This province became so used to getting wealthy off of oil and the benefits it provides that people here hate the idea of sharing that wealth and cutting into their own profits. It’s a bit like a wealthy business owner with three BMWs complaining that the carbon tax will make him have to downsize to just two BMWs.

Regardless of the virtuous claims of wealth redistribution, the NEP did worsen the economic reality for Albertans. Partly, the program came at a bad time: a recession was brewing due to outside forces. As well, the reduction in profits in the industry did cause many companies to reduce their presence in Alberta, exaggerating job losses. Robert Mansell researched how much of the economic hardships of the early ‘80s in Alberta were caused by the NEP. He found that, while a recession was inevitable, the transfer of wealth to the federal government alongside a reduction in exploration did deepen the recession.29 However, many Albertans to this day think the recession was caused by the NEP. Rather than deal with the reality that the Western world was going through a recession in the early '80s, Alberta's politicians made Ottawa the scapegoat.30 In fact, for part of his fight against Trudeau, Premier Lougheed turned off the taps supplying oil to Eastern Canada and barked at the federal government to "get off [Alberta's] front porch."31 Eventually, the program was scrapped in 1985, but the NEP lives on as a cautionary myth in Alberta to this day, even while the rest of the country has moved on. It was around the mid '80s that the economy was showing some signs of recovery, which seems to be how the new infrastructure and buildings completed in the late '80s first came to be.

And yet, just when the first glimmers of recovery were being felt, a second recession hit. In 1986, oil prices dropped again, plunging Alberta into another recession.32 One year later, the province had a 30% reduction in total revenue.33 This second recession was luckily short-lived, and by the end of 1987, the province was making strong employment gains that were maintained through the close of the decade.34 Despite this, growth was a half of what it was in the late '70s and it would take until the early 2000s for Alberta's unemployment rate to return to the extremely low numbers of the '70s.35

If any period in Edmonton’s late 20th century history was feverish, it was probably the ‘70s. The ‘80s, contrastingly, were bleak in a myriad of ways. So why do I have this idea of the ‘80s being a party, when the decades that preceded it fit that bill better? It didn’t come from nowhere, but this conception I have of the ‘80s reflects the fact that I have no memory of that time because I wasn’t even born. My idea of Edmonton in the ‘80s is completely fabricated. It’s a fever dream in a literal sense because it was created entirely in my brain, without any firsthand experience to back it up. Despite this, real events did inspire the fantasy I’d concocted.

The ‘80s Were Still Iconic

Economic realities are important. They are the base that our society structures itself around and influence people’s lives in tremendous ways. The economic situation at any given time can dictate if you have or you don’t and this shapes all sorts of decisions at individual and collective levels. There’s no doubt that for much of the 1980s, the economic situation was brutal in Edmonton and throughout Alberta. And yet, the ‘80s were still iconic. They might’ve been even more iconic than the ‘70s. So, what gives?

Well, despite the economic hardships of the era, the ‘80s were an important cultural epoch for Edmonton. It could be argued the period was the city’s greatest, culturally speaking, ever. No other time in the history of Alberta’s capital city commanded the same level of attention and intrigue from outsiders, cemented by iconic moments.

When Edmonton comes up to outsiders, if it comes up at all, people’s reference points home in on two things usually: the Oilers and WEM. The latter was largely built out over the 1980s while the former experienced its glory days during the same time. Both of these things play heavily into Edmonton’s outward identity and both of these things are rooted in the local culture of the ‘80s. Is it coincidental? Maybe. Gretzky could’ve been born a decade later and led the Oilers into a dynastic rule over the Stanley Cup in the ‘90s. That’s probably not true, but the point is that there’s nothing inherent to the ‘80s culturally that spawned the Oilers’ championships. Regardless, the ‘80s were when Edmonton’s two greatest cultural icons were their most iconic.

For the Oilers, their string of wins began in the mid ‘80s, well after Edmonton’s economic fortunes disintegrated. The Oilers would go on to win 5 NHL championships between 1984 and 1990, 4 of which with “The Great One,” as Gretzky’s still known, at the helm. The Gretzky era is still looked back upon fondly by Oilers fans and to this day Wayne is probably hockey’s most legendary player, an icon to hockey fans across North America and one of Edmonton’s biggest claims to fame.

But, the Oilers weren’t the only ones raking in sports wins in Edmonton. The city’s other major professional sports team, the CFL’s Eskimos also had a lot of success roughly around the same time. Their championship wins preceded the Oilers, though. The Eskimos began a streak of Grey Cup wins in 1978 (the same year they moved to Commonwealth Stadium) but continued into the early ‘80s. By 1987, both the Oilers and the Eskimos were the champions of their respective leagues. As with any city when their major sports teams are in the running for winning their league, Edmontonians got giddy and, collectively, spirits were raised by the feeling of success. After all, how many times do all the major teams in your city end up champions?

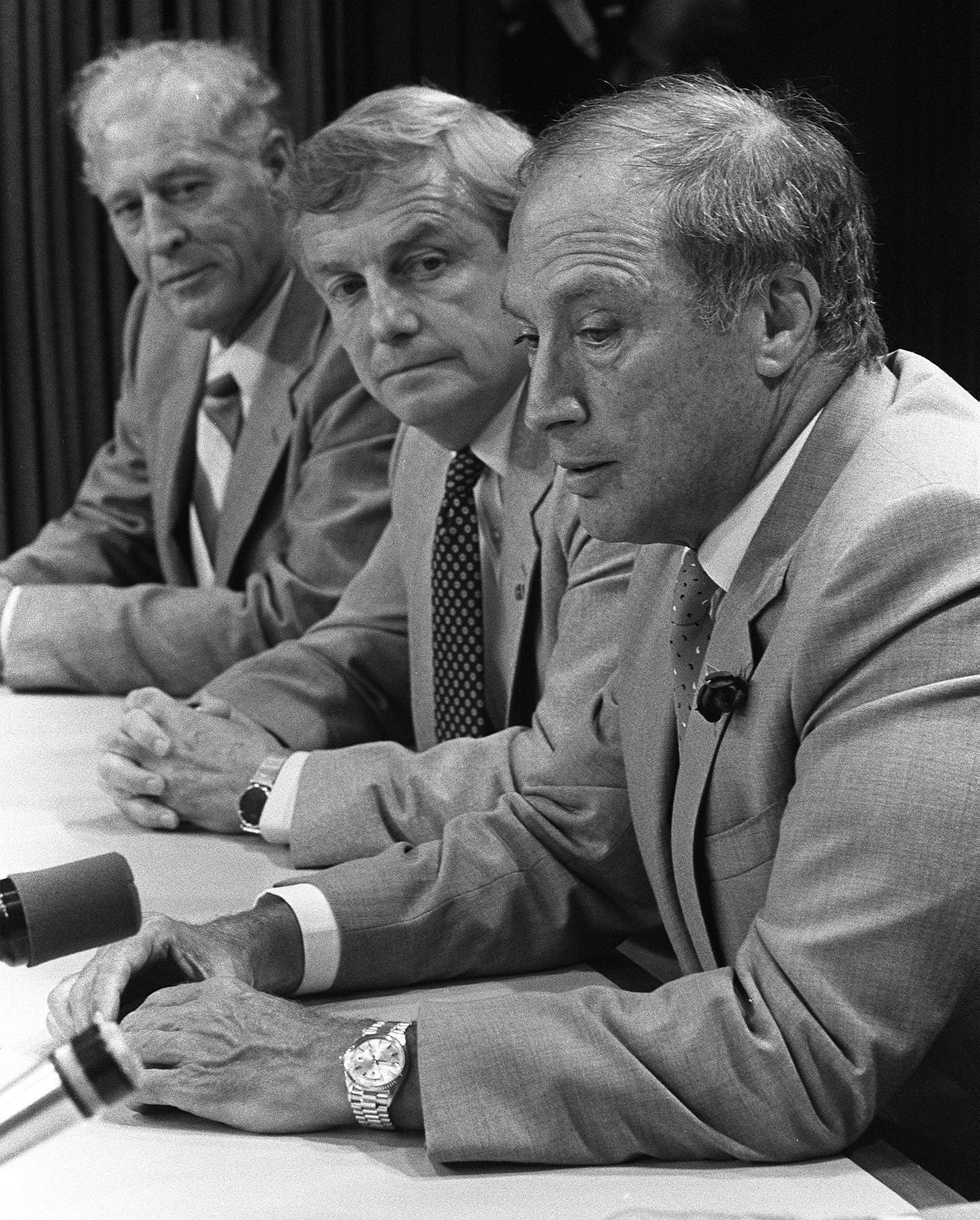

1987 was also when the “City of Champions” moniker gained steam as an emblem of Edmonton’s triumphs, which was another significant cultural marker from the ‘80s. Many people assume that the moniker had to do with how successful both of Edmonton’s major teams were doing then, but that's not entirely true. 1987 was also when the Edmonton tornado occurred — still the strongest twister in Alberta's history. To Edmontonians, it was “Black Friday,” the day that an F4 tornado ripped through eastern parts of Edmonton and Strathcona County over the course of an hour. This disaster would influence the Alberta government to develop a new public warning system, the first of its kind, which would use media outlets to broadcast critical information to viewers if disaster was anticipated.36 It was in the resilience of Edmontonians in response to the tornado that then-mayor Laurence Decore tearfully declared his city a “city of champions” while viewing the aftermath of the tornado’s destruction.37 The moniker had less to do with Edmonton’s triumphant sports wins and more to do with the city triumphing through hardship.

In the years following Black Friday, the City of Champions moniker would grow and feed the city's conception of itself, including being appropriated to encompass Edmonton's sports championships of the day. While the origins of the moniker’s identity originated in a natural disaster, as the years wore on, it became more associated with the Stanley and Grey Cup champions happening at the same time, which is why many to this day still think our sports-related successes are the reason the nickname used to don the gates of our city. Perhaps the most lingering relic of this appropriation is the old "Avenue of Champions" streetscape art on 118th Ave, denoting sports figurines outside the very place Gretzky brought the Oilers international renown. It's easy to understand why most think that “City of Champions” came from sports rather than disaster, when the City intentionally spent money on art that explicitly tied the notion of Edmontonians being "champions" to sports.

But what about WEM, which became a destination at the same time as the Esks and Oilers were raking in wins? The Ghermezian family, who'd already been involved in local developments in Edmonton, went big and bold in the early '80s when they built WEM. Although the site that the first megamall sits on had plans for a shopping centre since the early ‘70s,3839 construction only began in 1980,40 before the first phase was completed in September 1981. With just one phase down, WEM was already Canada's largest mall, boasting 220 stores.41 Think about that for a second — in less than 18 months, the largest mall in the country was built, which was only WEM's initial phase. This first phase had a quarter of the number of stores the mall now has and none of the dizzying attractions that were soon to be built, but it’s nevertheless impressive that such a massive structure was built so quickly.

And yet, the Ghermezians didn’t stop there despite the recession that started in 1981. Two more phases were completed — Phase II in 1983 and Phase III in 1985. While a fourth phase was completed in 1999, this was largely a repurposing of existing mall space, meaning that the entirety of WEM, Edmonton’s most well-known landmark, was built out to more or less its current footprint in the ‘80s.

WEM was a resounding success from the beginning. It turned the banality of suburban retail into an absurd fantastical space full of allusion and entertainment that hadn’t been seen before. Phase II and III brought the mall’s most incredible and ridiculous attractions to the public, including the Galaxyland indoor amusement park, the World Waterpark, and submarine rides. The Ghermezians built themed attractions modeled after other places too, including New Orleans, European boulevards, and Chinatowns. Many of these attractions still exist, even if repurposed. It was the first megamall, it was everywhere and nowhere at the same time, and for it to happen in a city as small as Edmonton is pretty amazing. The ‘80s were also the height of mall rat culture and WEM was the biggest and boldest expression of that cultural moment.

Another important but overlooked aspect of ‘80s-era Edmonton is that this was the decade when many of the city’s vibrant summer festivals got their start. If you think about the biggest, most prominent festivals in Edmonton, you’re almost certainly thinking about a festival that began in the 1980s. Folk Fest,42 the Fringe,43 Street Performers,44 Pride,45 the Works,46 Edmonton International Film Fest,47 and Taste of Edmonton48 all began between 1980 and 1986. Edmonton's Fringe was the first festival of its kind in North America and remains the largest outside Edinburgh.49 While it's hard to imagine Edmonton without these festivals, there was a time when the City of Champions didn't also go by "Festival City," another nickname Edmontonians have since taken up. But that identity had to be crafted and molded over time, and the beginnings of that were in the '80s, when the best-known festivals of today got their start.

Between the megamall, flourishing festivals, sports championships, and a devastating tornado that brought people together, the ‘80s were a period that Edmonton began settling into itself. No longer was it the Western frontier town of little significance, by the end of the ‘80s, Edmonton would even have its own folklore, of being a “City of Champions,” attached to it which strongly informed the city’s self-conception. I hesitate to say it’s when Edmonton matured, because the Edmonton of 2022 still doesn’t feel like a mature place in the way that Winnipeg or Quebec City do. Perhaps instead it could be viewed as when the city began an adolescence during which formative events occurred that weighed heavily on the city’s identity in subsequent decades. Edmonton ceased to be the hyper kid having a case of the zoomies that it was from the ‘40s through the '70s, but the cultural importance of the ‘80s contrasted the economic realities and ensured it was still a significant time in its own way. It’s hard to imagine Edmonton without these cultural emblems today, but they didn’t exist before the ‘80s.

However, I think it’s crucial to note that these weren’t the only things happening in Edmonton through the 1980s. On the cultural side, Edmonton also hosted the Universiade Games in 1983, while on the development side, new buildings were being erected, some of which were quite bold and expressive. Edmonton’s tallest building for over 35 years (because we’re not counting the antennae of Epcor from 2011) was Manulife Place, a shimmering post-modernist gem, was completed in 1983. The glossiest LRT stations in Edmonton, Corona and Bay, opened in the early ‘80s too. Of course, many of these developments were already underway before the recession began in 1981. Even WEM was conceived of before the crash and opened in its wake. The site of Manulife Place previously housed the King Edward Hotel, which, for a time before gay bars existed, was one of the more accepting places for queer Edmontonians to hang out provided you weren’t “too flamboyant.”50 The hotel was tragically destroyed by arson in 1978 and the site was razed in 1980, just before the recession, to make way for Manulife.51 The garish Bay and Corona LRT stations were also built out in a similar milieu, alongside the 1981 LRT extension to Clareview. It makes sense that the former half of the decade still contained some impressive development because they were overshoots of the '70s-era boom. But things didn't completely stall by the middle of the decade, either, even if a boom wouldn't return to Edmonton until the mid 2000s.

The Alberta economy started to recover in the middle of the ‘80s and although it wasn’t a full-fledged boom like the previous decade, development picked up. By then, some of the last remnants of Edmonton's Old Chinatown were destroyed to make way for Canada Place, a consolidation of federal government offices for Western Canada, which punched a splash of pink onto Edmonton’s skyline. In 1987, Edmonton’s own Eaton Centre opened downtown,52 which still includes the mesmerizing auburn skylight for the Delta Hotel. The mall was first conceived of in 1980 at the tail end of the oil boom,53 and was developed by the Ghermezians, the same people behind West Edmonton Mall, who were already successful local developers by then. They conceived of their collaboration with the Eaton family as a means through which to alleviate the problem they were causing: the decline of downtown retail due to rapidly expanding suburban shopping plazas.54 There was also what John Zazula characterized as a shopping mall boom at the time. WEM’s last major expansion occurred in 1985, cementing its status as the world’s largest mall, while downtown, the new Eaton Centre finally opened its doors in 1987.55 After Eaton Centre opened, the second phase of Kingsway Mall opened in 1988, the same year Mill Woods Town Centre opened its doors.56 Bonnie Doon also renovated and updated their interiors with a refresh that was done that same year. '88 was apparently a big year for malls in Edmonton! Across the street from the Mill Woods Town Centre, Grey Nuns Hospital was also completed in the late '80s, still the last hospital built in Edmonton. The LRT also expanded to Government Centre in 1989, while construction began on the Dudley Menzies Bridge, which would soon bring LRT service south of the river.57

Altogether, these buildings were some of the flashier architectural moments for Edmonton, emblematic of the post-modernist legacy still felt in the City of Champions. Post-modernist architecture is often quite loud, garish, and a bit silly, and the '80s to early '90s were the zenith of that particular design moment. Whether you're a fan of po-mo architecture and design or not, there's no doubt that it's quite impressive at times. As a result, regardless of economic uncertainties, Edmonton's built form from that epoch was quite daring. You saw the beginnings of po-mo loudness in the '70s with the Muttart and Citadel, but most of the structures from that time were more drab and utilitarian. It wasn't until the '80s that boldness became expected in architecture across the continent once again. So, if a building was being constructed, regardless of the social conditions of that particular place, it was likely going to be garish.

Even though the level of growth and expansion in the '80s paled in comparison to the 1970s, it wasn’t like nothing was happening in Edmonton development-wise, even after the market tanked. It wasn’t as frenzied but what came to the fore was some of the boldest architecture the city has seen. While WEM takes the cake for boldness, because of the po-mo aesthetics that were in vogue at the time, which prioritized a certain kind of flair, even less hyperbolic buildings expressed a boldness that wasn’t seen in the more minimalist mid-century designs from the boom years. However, the economic realities were still apparent and even influenced the construction of certain buildings. Christopher Leo uncovered how the Bank of Montreal manipulated city council to allow for the demolition of the Tegler Building after intending to designate it as a historic site in 1981. Along with the bank pressuring council by threatening to decamp to Calgary, the economic deterioration of the inner city likely pushed councillors to reverse their tune on saving the Tegler, deciding that the time was not right to take a stand against development when the downtown was losing so much to the suburbs.58

The decline in central Edmonton, through the '80s, came directly at the hands of new developments. While the pace of construction slowed, a lot of what was going up had a negative impact on downtown. Up until the 1970s, Edmonton’s core was the retail hub of the metropolitan area.59 At the beginning of the recession, between September 1981 and March 1982, 500 stores opened in suburban malls.60 WEM is the most obvious culprit, having its first phase open during this time, and there's no doubt that it permanently shifted the retail centre of Edmonton, but other shopping centres in the suburbs contributed as well. Often overlooked is Kingsway, a mere 6 blocks north of downtown's edge, which is still the second largest mall in the Edmonton area, first opening in 1976. This fixation on malls may seem a bit much in an era of big box stores and online retail, but for the era I'm focusing on, they were the social centres of their communities and a major economic boon. Thus, with the retail shift to suburban malls, Downtown Edmonton ceased to be the social centre of the city in the same way it had always been by the '80s. The new office towers built in the early '80s caused a glut in space that, coupled with the recession, meant office vacancies were also high -- reaching 24% the same year Manulife Place opened.61 Downtown was obviously getting more desolate. Another prominent vibrancy-killer for the city centre was one of Edmonton's more innovative projects: the LRT. While an excellent asset today, the construction of the underground tunnel down Jasper Ave, the traditional retail main street for Edmonton, meant that the street was closed off and difficult to navigate for years, causing a decline in traffic. This precipitated a loss in revenue for businesses, forcing many to close, further contributing to the emptying of the city's core. The job losses of the decade also meant less people were spending money at downtown attractions because they couldn't afford to do so. If the '80s were dark in Edmonton, it was doubly so for downtown.

If 1947 to 1981 was a party, then perhaps the ‘80s were the afterparty. It wasn’t as big of a bash, and there was a darkness behind it, but like any good afterparty, it was still incredibly seductive. Running on the fumes of the ‘70s boom, the early ‘80s produced many new landmarks for Edmonton, while the Eskimos utilized the new Commonwealth Stadium for their Grey Cup successes. With the Oilers gaining steam and producing a literal legend as the decade wore on, Edmonton had its greatest cultural moment. WEM was the icing on the cake. The ‘80s were still a bash, but a different one than the ‘70s. Instead this afterparty coalesced more along a few key players, but it was arguably just as loud and fun. Compared to the post-WWII party, the ‘80s recession-addled afterparty was more about cultural moments of relevance than economic development. In spite of how gloomy things were for a lot of Edmontonians, the 1980s were Edmonton at its most iconic, a period that lives on with some degree of fondness thanks to the legacies of the city’s most well-known attributes.

The Nadir

Ok, so the ‘80s were iconic, but that still doesn’t entirely explain my fascination with the era. It was still a dark time. Why have I been so quick to romanticize such a hard period? Because, depending on your perspective, what came after was arguably even worse. This was the Edmonton I grew up in: the stagnant, almost comatose ‘90s and early-to-mid 2000s when my hometown became a has-been, left in the dust by Calgary and succumbing to a hefty inferiority complex.

The early ‘90s were alright. Similar to how the early ‘80s were full of the last gasps of the oil boom from the decade previous, the early ‘90s held onto the momentum of the late ‘80s. The Oilers had their last Stanley Cup win in 1990, after Gretzky decamped to Los Angeles, the same year Commerce Place was completed, which was the last new office building and shopping mall of the century. Londonderry Mall renovated itself in perfectly po-mo blue in the early ‘90s, too.62 By 1992, Edmonton’s new city hall finished construction, further entrenching the city’s pyramid fascination that began with the Muttart in 1976. That same year, the LRT extension to the University of Alberta was completed which, like Commerce Place, would be the last construction of that kind for some time.

At the tail end of 1992, Ralph Klein was ushered in as Alberta’s new premier. If we had to pinpoint a specific night that the ‘80s finally came to a screeching halt in Alberta, it was probably December 14th, 1992, the night Klein succeeded Don Getty as premier by winning the PC leadership race a week prior. His reign at the legislature lasted until the same date in 2006, continuing the dynastic rule of the PCs into the millennium. With Klein, an era of budget cuts began for Alberta that hurt Edmonton's economy quite a bit and left the city in a sleepy trance. Of course, there’s rarely such a hard division between epochs, and some infrastructure projects, such as a big upgrade to the Whitemud, which started construction in 1990 but opened in late 1993, was completed after Klein's succession.63 This project wasn't unlike the projects completed in the early '80s in a different economic reality from when they broke ground. But, for the sake of neatness, 1992 is as good a line as we'll get between the before and after, and the election of Klein set the mood for the rest of the decade in Edmonton. Although the Whitemud wouldn't be the last high-profile project built in Edmonton before the year 2000, big development became significantly more scant after Getty stepped down.

1992 was also a transitional year between ‘80s and ‘90s sensibilities in the wider cultural milieu. It was the year that grunge began to take over the mainstream, influencing music, fashion, and youth culture. With this shift, the shoulder pads and hairspray went out, along with the vapid materialism that they were often associated with, and in its place were more unkempt and natural aesthetics alongside a backlash against the commercialization of the previous decade that pervaded pop culture. And thus, this was also a period of cultural shifts as well, as Gen X was coming of age.

Continuing with the theme of shifts, in 1992 and 1993, the American and Canadian federal governments, respectively, elected more liberal leaders in contrast to the right-wing governance of the ‘80s. However, that distinction was merely superficial, as these centrist governments were very intoxicated by the same ideology of neoliberalism as their opponents. A major facet of neoliberal ideology is a faith in market-based solutions to problems. This, in conjunction with individualistic rhetoric and further consolidation of power, means that austerity becomes a way of life under this doctrine. Thus, the project of trickle-down economics that began in earnest with Thatcher and Reagan continued with the political rule by parties supposedly antipodal to them. In Canada, Chretien would absolve the federal government of any responsibility to provide public housing, while in the States, Clinton would introduce his infamous “tough on crime” bill that disproportionately affected working class black communities and furthered an agenda of mass incarceration and harsh sentences.

During the 1993 provincial election, Ralph Klein campaigned with a neoliberal platform rooted in austerity and balancing the budget, which the PCs easily won. With “King Ralph” in power, Alberta saw sweeping cuts to taxpayer-funded services including healthcare and education in an effort to get the government out of people’s lives. In fact, provincial spending was cut by 20% in the following 3 years while “workfare” programs replaced regular welfare.64 Under workfare, welfare applicants are assessed based on their perceived ability to work, and are put to work in order to access benefits if they were deemed fit to work rather than just providing essential services to people who need them. Overall, the dramatic spending cuts made the lives of Albertans worse — wait times worsened65 while Klein forced public-sector workers into pay cuts and layoffs.66

Eventually, the provincial government made good on its promise to balance the budget, and by the mid-2000s, Alberta was seeing a surplus of revenue.67 As a thank-you to its populace, the Province announced a $400 rebate, colloquially known as “Ralph Bucks,” for every Albertan. After spending a decade slashing services and deteriorating the quality of life for Albertans, our paltry gift would begin arriving in mailboxes in January 2006. Of course, despite the government drowning in revenue to the extent of spending $1.4 billion on these rebates, those who couldn’t get a hip replacement in time didn’t have their situation ameliorated and those who lost a job weren’t offered one once the budget was balanced.

The irony is that when Klein was mayor of Calgary during the ‘80s, he oversaw the construction of the Saddledome and was a proponent of C-Train expansion and pushed the province for funding.68 But by the time he became premier, Klein’s tone had reversed and his austerity and privatization agenda hurt Edmonton a lot more than it did Calgary, which is far less reliant on public funding to drive the local economy. Through the ‘90s, the PCs pursued privatization wherever possible, both before and during Klein’s reign. A great example of this is when the province privatized its public telephone company — Alberta Government Telephones (AGT) — in the early ‘90s and became Telus. It later bought and therefore privatized EdTel in 1995, which was the public telephone provider for Edmonton.

Edmonton was also losing some major head offices in the '90s. Back in the ‘80s, the Bank of Montreal threatened to keep its headquarters for Alberta in Calgary as a way to push for the demolition of the Tegler.69 But by the '90s, the private sector was quickly decamping to other cities. After Telus acquired BCTel during a round of privatization in British Columbia, the company moved its headquarters from Edmonton to Vancouver. In the mid '90s, Shaw also left the City of Champions, for Calgary.

Downtown in general wasn’t looking so hot either. As a result of Klein’s public sector job cuts, Edmonton’s centre had less people going to lunch, stopping for a drink after work, or grabbing a gift at a boutique, which had a detrimental impact on businesses, many of whom were forced to close. For some, Jasper Ave was referred to as Casper Avenue, a reference to the ghost town vibe of Edmonton’s main street at the time.70 This, of course, was merely a continuation of downtown decline from the '80s, when malls cannibalized central retail and LRT expansion turned Jasper Ave into a prolonged construction site.

While the ‘80s undoubtedly were economically perilous, the ‘90s and early 2000s seemed darker to me. Of course, this is biased by my lack of firsthand experience of the '80s, but that decade still had a fair amount of public spending, including big ticket stuff like LRT expansion and the construction of Canada Place. It was also the last time Edmonton felt more culturally prominent than Calgary, emboldened by the Oilers, Eskimos, and WEM. After Klein’s ascension in 1992, public sector investment flatlined. It wasn’t just that there wasn’t a healthy amount of people employed downtown or LRT expansion — road maintenance became weaker as transportation spending was cut from $70 per person in the '80s to $25 per person in 1993.71 This meant more cracked roads and municipalities bearing the brunt of crumbling infrastructure. On the private side, major companies left and there was a general malaise. As dark as the '80s were for many, the ‘90s seemed to compound the already depressed state of the economy and lacked the splashes of cultural relevance that its predecessor had. The conditions were so bad that Edmonton’s population shrank for the first and only time since the Great Depression between 1993 and 1996.72 This was the Edmonton I was born into. By the early 2000s, Calgary had supplanted Edmonton as Alberta's largest city, and the Heart of the New West seemed to be chugging along better than my hometown.

Anemoia

For many, Alberta conveys an image of boldness, boosterism, and bravado, but in the ‘90s and 2000s, Edmonton lost that. It’s hard to stress how different Edmonton felt back in the ‘90s and 2000s to people who’ve only known the city over the past decade or so. Edmonton was very sleepy and stagnant — it no longer had any delusions of grandeur and in fact developed a sizable inferiority complex. We weren’t as good as Calgary, and we knew it. Meanwhile, Calgary was busy aspiring towards larger centres like Vancouver and Toronto and our southern neighbour became the undisputed Metropolis of Alberta in the collective consciousness. Edmonton was a mere afterthought. It’s no wonder I became fascinated with what came before, which, over time, grew into anemoia, a neologism that refers to a nostalgia for a time not experienced.73

As much as Edmonton has moved on from this sluggish time, the scars of the doldrums can still be seen today. After the downtown railyards were removed between 1988 and 1996, the city’s heart was left with huge, gaping voids. While some of the earliest redevelopment came with a new central campus for MacEwan University, that only took out one of many chunks. Faced with economic divestment that left little interest in city centre development, the City took what it could get, approving whatever would fill those massive blank spaces. The result is the cheap and suburban-styled big box shopping centres and ugly stucco-clad True North Properties condos along 104 Ave and 109 Street, largely built out over the late ‘90s and early 2000s. One of the developments, creatively dubbed “Railtown,” is essentially a suburban gated condo community (with literal fences around each building) right in the heart of the city. Similarly, the big box layout of Unity Square along 104 Ave makes you think you’re at South Edmonton Common, with the looming high-rises in the distance being the only indicator that you’re not. While they are evidence that development didn’t completely halt in the core, they lacked any of the bold or whimsical designs commonplace just a few years prior at the start of the ‘90s. Instead, they were mediocrity at its finest and their car-centric designs were emblematic of how down and desperate things had become, as this low-grade urbanism was all developers deemed central Edmonton was worth. Vancouver, by comparison, was doing Yaletown during this time. While I have many complaints about that neighbourhood, at least it’s walkable and has good public spaces. Yaletown was also at the forefront of a new type of urban planning, dubbed “Vancouverism,” that marked a shift away from car-culture, instead being focused on transit, density, and walkability and one whose designs have influenced cities throughout North America since. Vancouverist developments like Yaletown were the antithesis of what Railtown became.

The Edmonton I grew up in through the ‘90s and early 2000s was a city of inertia and even when there was movement, little of it was noteworthy. I think many folks looked backwards because of how anemic the present felt. While the suicidal job losses of the ‘80s ceased to be a thing by the turn of the millennium, it didn’t feel like a lot was going on. WEM’s Phase IV, built in 1999, complete with a fire-breathing dragon, was arguably the developmental highlight, alongside the completion of the Winspear Centre a couple of years prior. But, otherwise, no LRT was being built, no new office towers, only some suburban-style development, both on the edge and in the heart of town. There wasn’t any cultural significance to keep people entertained, either. So, it’s easy to understand that, in this malaise, people looked back to the last time big things were happening in Edmonton. That just so happened to be the 1980s, particularly with regard to the sports championships, and thus people’s nostalgia often fixated on that.

I think this milieu is where my fascination with the ‘80s found its origins. I remember this feeling of not being in on the reference when people would talk about their relatively recent memories of Gretzky during the early 2000s. These were the glory days of the Oilers, and in a hockey-crazed town like Edmonton, that’s a big deal. I’d missed out on that time myself, but the way people talked about it only fuelled my intrigue. On top of that, I grew up in the shadow of WEM, which was still a big deal for locals and continued to serve as something that put the city on the map. And of course, 25 years ago, WEM was significantly more ‘80s-styled than it is today (although some places, like Galaxyland, had already been renovated in the ‘90s), and so I came to unconsciously associate those awesome aesthetics with a high point in Edmonton’s fledgling sense of place. The mall was a bragging point for friends on the northside who were jealous I lived somewhat near it, in all its absurd magnificence. West Edmonton Mall strongly informed my idea of what a mall ought to be like, and no mall I’ve visited to date has lived up to the high bar the Ghermezians created for me.

But, these emblems of Edmonton likely weren’t the only cause of my strange fixation on the gaudy ‘80s. My childhood was also a bit unorthodox. I had parents who were regularly mistaken for older siblings; their youth meant that none of their peers had any kids for me to play with and so I spent a lot of time around adults when not in school, particularly because I didn’t live close to my school and thus nowhere near my friends to hang out after school or on weekends. As I was surrounded by and thus often influenced by adults, the stories being told were often of an older sort than from those around my age, which meant that the tales that stuck out were often from times before my own. The ‘80s were also the decade of both of my parents’ childhood and adolescence, and as someone who often spent a lot of time with them, partly because that’s what kids do and partly because of the geographic situation, I gravitated towards their vantage points and interests, which were influenced by the era they grew up in. I still remember my mom’s retelling of her time at K-Days when Black Friday happened and pictures of my dad in Holland in the early ‘80s at my grandpa’s apartment that stared at me for a quarter-century whenever I was over. I also grew up with vignettes of ‘80s pop culture: my grandma would dance problematically to “Walk Like an Egyptian” while my dad was frustrated by how hard it was to find Adventures in Babysitting on DVD.

It’s normal for kids to be influenced by the eras their parents grew up in. But, as a millennial who usually had the youngest parents in my class, the era of my parents was a lot later than the Boomers my friends had for moms and dads. Coincidentally, my parents’ upbringing through the ‘80s was also the last time Edmonton was more culturally relevant than Calgary, the last time the city had any inkling of boldness, and the most iconic period for its most iconic institutions. People didn’t talk about the recessions and job losses of that epoch when I was growing up, it was more about the mall, sports teams, and the tornado, while looking around the city, even if more was built from the ‘70s, the ‘80s were the last time there was a significant amount of development. Naturally, I had a sugar-coated idea of the ‘80s in Edmonton until I was an adult. My parents, the main reference points for looking at that decade, were also kids then, and thus weren’t as up on the economic realities, and were fortunate enough to have parents unharmed by the recessions flowing through Wildrose Country back then.

Now, it’s not like I was obsessed with the ‘80s as a kid. I didn’t think about the mall or Gretzky or various pop culture moments of the era that deeply. The ideas I have now came about as I grew older and crystalized in adulthood. When I was a kid, my fascination with ‘80s moments were with isolated incidents that may have happened around the same time but were only conected incidentally in my brain. WEM might have been cool to a 10-year-old me, but I wasn’t thinking about how ‘80s the space was.

By my late teens, there was no doubt in my mind, for better or worse, Edmonton was an ‘80s city. I started connecting the dots and became more aware of how the period was incredibly formative for Edmonton. But also, this resonated with my biased background that was riddled with ‘80s iconography. The ‘80s were, from the perspective of my 2000s childhood, the last time it felt like anything happened here, a bookend to the mid-century boom, or a transitional period between the highs of the mid 20th century and the lows of the ‘90s. As such, that period was and still feels impressive to someone completely divorced from the darkness that time also created for Albertans. Of course, many old enough to remember the ‘80s over 20 years ago also severed their impression from reality, retconning the decade into something better by reminiscing over the highlights.

Through the 2000s, the lack of anything happening meant that Edmonton was a punching bag for its datedness, derided specifically for being “stuck” in the ‘80s. And to be honest, despite having strong associations with the iconography of the ‘80s, I too held contempt for Edmonton’s inertia, especially as I grew older and started realizing how lacking the city seemed compared to other places.

Surprisingly, there does exist a pop culture artifact that accurately portrays the stuck-in-the-‘80s vibe of Alberta in the early 2000s, before the next oil boom happened. The 2002 satirical film Fubar is a zany look at a period when many people in the province were living in the past. The film focuses on a couple of headbangers — Dean and Terry — and their everyday shenanigans. It’s low brow in the best way and extremely dudes rock. Fubar captures the unpretentious and ridiculous aura of young white working class Alberta in the early 2000s while somehow being the best commercial for Pilsner I’ve ever seen. While the film is set in Calgary, it feels just as, if not more, relevant to Edmonton. Despite what was said before, Calgary wasn’t smoking hot through the ‘90s either, and only from a place of experiencing an even deeper nadir like Edmonton did things seem significantly better there. Our southern neighbour also had cultural moments, like the 1988 Olympics, to look back on from the ‘80s. So there was a collective reminiscence through the province that I’d argue was stronger in Central Alberta, but nevertheless permeated the province broadly, and that’s precisely what Fubar encapsulates.

What’s most striking about the two lifelong friends who anchor the film, beyond their demeanour, is the way they dress. Both have gnarly mullets, loose light-wash jeans (now called “dad jeans”), while one has a penchant for vintage sunglasses and the other is still rocking a moustache in a time when that facial trend had been relegated to the “creep” category. They were clearly something out of the late ‘80s and could’ve easily served as extras in a Def Leppard video. As anachronistic as Dean and Terry look, especially against the relatively modern attire of filmmaker Farrel, they were also a reflection of the cultural currents in Alberta in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. Just as Edmonton was nostalgically yearning for its cultural glory days, so too were Dean and Terry eager to live in the past and refuse to grow up. There were a lot of people like Dean and Terry in Edmonton and throughout Alberta back then, which is why the film feels so visceral to me. The film encapsulates that nostalgia Edmonton was stuck in, unwilling or unable to move on from the ‘80s because there was nothing going on to propel us forward and give up the brass and mullets.

When we look back in time, we’re often actively building fantasies in our head. Nostalgia clouds our judgment with emotions, while time rots memory, and so our ideas of the past aren’t objective reality. When we look back, we never actually go back. The 2022 film Aftersun is a brilliant rendition of the limits of nostalgia. The film has nothing to do with the ‘80s, but nevertheless perfectly captures the impossibility of reaching the past. Aftersun is a series of vignettes about a trip a father takes with his preteen daughter in the late ‘90s. It’s shot from the perspective of the daughter, now a full-grown adult, trying to piece together the past, but it’s always incomplete and fragmented. This is how nostalgia works, not as a true wormhole back in time, but rather as a hazy reconstruction of the past that’s often inaccurate. Regardless, the fantasies we erect in our minds that indulge our idea of the past end up strongly informing the way we conceive of the past. How many people’s idea of the ‘80s is informed by works of literal fantastical fiction like Stranger Things over objective truths (if there’s even such a thing)?

Many people nostalgically re-imagine the past. It’s what Edmontonians did when I was a kid. The job losses and suicide hotlines were omitted in favour of Laurence Decore’s moniker and the Grey Cup. This made the ‘80s seem more amazing me than they actually were, as someone who’d never experienced them. This was likely the catalyst for my anemoia-rooted fever dream of the ‘80s. Despite this, when you comb over history, it’s pretty clear the ‘70s were much more objectively feverish. No matter the facts, the ‘80s will always seem more iconic in my mind. I stubbornly cling to this narrative, even though reality is more nuanced than this. For all my talk about how terrible the ‘90s were in Edmonton, it wasn’t all bad. Despite me waxing on about the dearth of significant cultural generation at the time, the decade is seen by many as the pre-gentrified cultural peak of Whyte Ave. The strip hit a momentum in its revitalization and boasted a range of quality of independent businesses that no longer exists. Additionally, not long ago, I learnt that WEM’s Galaxyland, which had one of my most cherished style palettes at the mall before its recent renos, got the unique aesthetic I’m most familiar with in the ‘90s, not the ‘80s like I’d always thought. This is all to say that my ideas of the past are extremely flawed too, and that goes double for eras that I don’t even remember.

To be sure, there are real things that back up my nostalgic fever dream. While I’m critically examining the holes in my long-held belief, I still have to admit that the good bits that the dream is based on were real. In a cultural sense, the ‘80s were iconic for Edmonton, even if the decade wasn’t in other ways that impacted people’s day-to-day lives. But my omission of the bad bits created a fantasy in my brain about the past, not unlike the genuine nostalgia people create about their past, even though it isn’t my past. Thus, even today, my idea of Edmonton is still firmly rooted in moments from the 1980s, before Klein took over in the ‘90s and unleashed even more havoc on my hometown. It’s because of how weak Edmonton felt through my entire upbringing that I longed for some iconic past that I never experienced and that was never as candy-coated as it seemed. Or at least that’s the narrative I concocted.

The Resurrection

And then, things changed. Even in my biased perspective, I don’t think Edmonton exudes the ‘80s anymore. Today, a lot of the landmarks and moments of the past are being bulldozed over as the city re-imagines itself. The reason for the change is pretty straightforward: the economy boomed again. There’s also the fact that, unlike the ‘90s and early 2000s, the ‘80s aren’t a recent cultural memory anymore, so not only have Edmontonians been distracted by newer ventures, the time gulf between now and then is so much greater and so it’s not as readily looked back upon.

The boom started in the mid 2000s, when oil prices sharply rose. At the same time, Stephen Mandel won the 2004 mayoral election, and ushered in a new era of relatively forward-thinking politics for Edmonton. Still, this boom period was largely focused on new sprawl, including expanding the Anthony Henday ring road, but it also involved the first LRT expansion since 1992. Of course, it was a mere one-stop extension, rather than a multi-stop extension or a new line altogether, but it was an improvement over the nothingness of the ‘90s and early 2000s, and they were planning for more LRT that would open by the end of the decade. In this stage of the boom, Edmonton still felt fairly sleepy, even if its edges were growing like dandelions again and it was no longer as affordable as it had been a few years prior.

By the late 2000s, the boom had momentum that saw more high-rise development downtown again. This included the Icon condos on 104th Street, dubbed the “tallest and most elegant residential towers” in Edmonton, and Epcor Tower, the first office tower to break ground since the late ‘80s with Commerce Place. Speaking of 104th, this was also when the seeds of the municipal government’s investments into improving that street were starting to bear some fruit, particularly with the successful outdoor City Market (which had moved to the street in the mid 2000s) that closed the street to cars every Saturday during the warmer months. Meanwhile, malls like Kingsway and Southgate embarked on expansions and the LRT was extended much further south in 2009 and 2010. I remember being really proud of the LRT extension to Century Park when it opened, like a beacon of progress that showed Edmonton was shaking off the dust that had accumulated over 2 decades. The City was also starting to think big again with the decision to close the City Centre Airport in 2009, something that would soon allow for some rapid transformations in Downtown Edmonton.

Of course, there was the Great Recession. But unlike in the US, its effects were never as severe, and cities like Edmonton bounced back quick after a short dip around 2008. By the early 2010s, a new oil boom was starting, and there was a momentum in Edmonton that hadn’t existed in my lifetime. Maybe it wasn’t quite as big as the ‘70s and ‘80s, at least not yet, but it was something. It’s ironic that then-mayor Bill Smith campaigned in 2004 on “keeping the momentum going”74 before being defeated by Mandel because I occasionally wonder where Edmonton would’ve ended up if it kept on the status quo path that Booster Bill exemplified. I don’t think I would’ve been graduating high school feeling like things were beginning to happen in exciting ways for my hometown.

As the boom continued, Edmonton elected an even more progressive (at least superficially) mayor and council in 2013 with Don Iveson at the helm. The City planned vast LRT expansions while the last flights out of the City Centre Airport happened. The closure of the old airport meant central Edmonton was relieved of its decades-long height limit. Meanwhile, the City began talks with Daryl Katz, the Oilers’ owner, regarding the construction of a new NHL arena downtown. That resulted in what was perhaps Edmonton’s boldest vision in 25 years — Ice District. Not only would this new downtown entertainment district hold a grand new arena, it would also have not one, but two towers punch well above downtown’s old height limit. One of these towers, Stantec Tower, before it was known for falling panes of glass,75 became the tallest skyscraper in Canada outside of Toronto. That’s right, taller than anything in Calgary. During the 2010s real estate boom, skinny homes76 began to infect Edmonton’s mature neighbourhoods with gentrification, condos proliferated in Oliver and Downtown, and old brownfield sites on Whyte were redeveloped. Of course, the city still sprawled too, so much so that it won its first major land annexation since 1982.

Even the mid 2010s oil slump couldn’t stop Edmonton’s momentum. In a twist of fate, Calgary’s economy, more based around private oil firms and oil sands speculation, would stall while Edmonton kept marching forward. In fact, Edmonton began growing faster than anywhere else in the province.77 Tales of the ghost town on Stephen Ave would trickle up the QEII but felt largely foreign, which felt like a reversal of the fortunes of the ‘90s. Now Edmonton, less tied to corporate natural resource development, was faring better. Of course, Calgary never ended up like Edmonton in the ‘90s — it still grew, it just had less office towers under construction and those that came to market had high vacancies. At the same time as the oil slump sank into Southern Alberta, in 2015 Alberta shockingly destroyed its 44-year-long PC dynasty and elected a New Democrat (NDP) government to power. Being that Edmonton is Alberta’s NDP base, this also marked a shift towards a more Edmonton-centric legislature, after decades of Calgary-centric legislatures (minor blips like Stelmach notwithstanding).

With all of this development in motion, Edmonton’s vibe began to shift too. I started noticing the city shed its inferiority complex and slowly regain some of its lost confidence. Maybe it wasn’t better than Calgary, but Edmonton was at least its peer again. Most surprisingly, it wasn’t as bewildering to come across someone who earnestly liked Edmonton.

So where do the ‘80s fit into my idea of Edmonton, when Edmonton itself was moving on? The city even stopped officially calling itself the City of Champions, while WEM began renovating away its kitschy 20th century vernacular. But it wasn’t Deadmonton anymore — a pejorative that only lives on as a haunted house attraction every October now but once sardonically poked fun at how dull and sleepy Edmonton seemed. The irony is that even though Edmonton started thinking big and doing interesting things, I still had a sense of anemoia towards the ‘80s. I still yearned for that past I was never part of and still associated Edmonton with that era. It turns out, Edmonton doing the stuff I criticized the city for lacking when I was an adolescent wasn’t all I thought it would be.

The Underbelly of Progress

It’s a strange paradox that, after endless stagnancy and yearning for change, when that change finally arrived, it made me nostalgic for the previous status quo. But it makes sense when you consider the fact that I had my formative years in a particular iteration of Edmonton that was rooted in monotony. Whether this was good or not is a conversation for another day; the important thing is I became very comfortable with that complacency. When that status quo was upended and intentionally dismantled, I was initially excited, but the City of Champions became something else, and I became uncomfortable. Thus, there’s still a twinge of nostalgia I have for the sleepy Edmonton of my childhood that had the shadows of the 1980s looming large.

It’s funny looking back 10 years to when I welcomed the change. While there was a part of me that lamented missing out on the Oilers glory days, I still don’t really care about hockey, and was disdainful for how dated Edmonton felt at times. The sparks of change in the late 2000s and early 2010s felt refreshing, but by the mid 2010s, enough change was building up and my hometown began to no longer be as recognizable. I spent so much of my life in an Edmonton that was immune to change and when that shifted, I became uneasy. Edmonton’s skyline was shimmering with new glass skyscrapers, but it was also foreign — the new shapes produced by the Ice District alienated me. The city was turning into something unrecognizable, which over the years fed my nostalgic tendencies. Maybe the Edmonton I grew up with was boring, but it was my boring city; whatever it was turning into in the 2010s wasn’t the city I knew.

Taking emotions out of it, of course the Edmonton of today has made some serious attempts at improving the city and shifting the culture towards something more optimistic. City council is more dedicated than ever to building a bike lane network, massive LRT expansion is underway, and there’s a shifting focus towards densification and infill. The City is planning ahead for a population within city limits of 2 million, with a goal of housing 50% of new units within existing neighbourhoods78 (it's already reached 30% as of 202079) and Edmonton became the first city in Canada to eliminate parking minimums for future development.80 Edmonton's also creating striking new landmarks, such as the new Walterdale Bridge, rather than resting on its laurels. There's much to be commended and Edmonton is, in many ways, better than it was 20 years ago.

And yet, what gets glossed over is that in other ways, it’s worse. It’s great that Edmonton is shifting the focus towards infill and density, but that’s causing its own problems. Within Edmonton’s mature neighbourhoods, skinny homes have proliferated as a result of lot splitting. While these are ostensibly good for building density in Edmonton’s large lot mid-century neighbourhoods, they are extremely cookie cutter and the quality of materials used often isn’t on par with what they’re replacing. They’ve also been encroaching on working class neighbourhoods and causing surrounding land values to rise, slowly pricing out working class communities that’ve called their communities home for decades. Patrick Condon, a UBC planning professor, rightly criticized the density-no-matter-what, stating how increased density doesn’t necessarily equal increased affordability. The cost of living and especially of housing has only skyrocketed in the last 15 years in Edmonton, and those skinny homes aren’t going to the city’s marginalized. Condon noted that when someone buys a lot, tears down the house and builds a couple units on top of it, there may be an increase in density, but the price of those new units are almost always more expensive than the single family home they replaced.81 If Edmonton continues on this path of densification, it may push the city to become even more unaffordable. The reasons for why infill tends to be pricier is rooted in the market-centric way of providing housing in our society. In particular, the way that the potential for increased density with new construction can make a parcel of land more attractive to development, because there's more people to potentially sell to on the same plot of land, thus increasing land value.82

Affordability is becoming a huge problem for cities. It doesn’t really matter that a city keeps adding more fun things to do if you can’t afford the city itself. This is a problem plaguing cities from Toronto to San Francisco to Melbourne, but it’s also creeping into cities often considered “cheap,” like Montreal, Hamilton, Winnipeg, and, of course, Edmonton. The city that no longer wishes to be referred to as champions is doing the same thing every city in North America is doing: chasing capital in the hopes that they will bring an increase in land values and therefore property taxes because our austerity-addled era has left cities to fend for themselves, rather than rely on provincial and federal funding. Under neoliberalism, cities are now competing with each other like never before to attract investment. This was perhaps most dramatically seen in Amazon’s open call for cities to pitch themselves to the company for a second global headquarters in 2017. There’s often a belief that with increased tax revenue from swollen property values, cities will be better able to provide supports to the more marginalized. But providing those things is usually antithetical to attracting capital, and cities are endlessly trying to grow their tax base, and so are forced to endlessly attract capital, and aren’t able to take a breath and focus on other things.83 As a result, municipalities can be quite careless at the policy level when it comes to dealing with rising unaffordability.

The ongoing pandemic hasn’t helped matters, either. In Edmonton, due to oppressive economic and social conditions, the unhoused population has doubled over the course of the pandemic,84 while an ostensibly progressive council continues to make hollow land acknowledgements and little else.85 Despite commitments to building more supportive housing, the City has chosen a top-down approach, such as violently expropriating the Indigenous-led Camp Pekiwewin in Fall 2020. The camp was built in response to the City's closure of a nearby shelter as well as Edmonton Police Services' (EPS) aggressions towards the unhoused, including slashing and pepper-spraying tents.86 There were numerous complaints from more privileged classes about the presence of Pekiwewin and so the City's response was to forcibly remove them via EPS.87 Council could even feel morally justified with this position, despite it happening in the wake of the George Floyd protests, because the City offered to relocate Pekiwewin residents to local shelters.88 However, what this "solution" ignores is the fact that there aren't enough shelter beds for the 2,000 unhoused people in Edmonton and that many of those living in Pekiwewin spoke of how much safer and more welcomed they felt at the camp.89 Rather than letting community-based solutions flourish, Edmonton chose to paternalize marginalized people and force them into the state's own control. When Prairie Sage Protectors returned to the site of Pekiwewin to honour a camp volunteer who passed away at the hands of EPS, half a dozen cops showed up and threatened them with arrest.90 Since then, Edmonton re-opened access to the camp's site but not for the unhoused. Instead, this year, the fenced off site that held the camp was turned into a parking lot for settlers to celebrate Canada Day.91

So it’s not only that Edmonton’s look has become increasingly alien, but also that there’s a clear darkness to the ostensible progress. Alleged markers of innovation are often empty at best and violent at worst. What happened at Pekiwewin isn't an isolated incident — at the beginning of 2022, it came out that transit officers forcibly ejected unhoused people from trying to stay warm in LRT stations92 during the longest cold snap since 1969.93 Displacement, whether through market forces such as gentrification or through the direct violence of carceral systems, is the name of the game in our contemporary age. I want Edmonton to stop sprawling too, but not if it merely displaces the working class for vertical suburbs of wealth.

A Stuck Culture

In a more superficial sense, Edmonton has also deteriorated aesthetically in the past 15 years. You could argue it started in the late ‘90s, when it felt like True North Properties was the only name in town. The city’s architectural quality hasn’t been the same since King Ralph was sworn in. It’s not just that buildings look worse, they’re also structurally cheaper and shoddier on average.

Despite my reticence for utilizing real estate gentrifier slang like “character,” there’s no doubt that the new Edmonton has paved over a lot of it in the name of growth and progress. And in its wake was something paradoxically more boring than the sluggish Edmonton I grew up with. That isn’t just an Edmonton problem, though. It’s really a condition of our contemporary moment, when buildings are built as disposably as clothing and electronics. Everything is soulless and impermeable EIFS, while we’re obsessed with banal minimalism in an ironic juxtaposition to our maximal consumptive habits. The only respite from this is an endless rehashing of styles from the 20th century, feeding our collective nostalgia.

I hope Fukuyama was wrong about neoliberal capitalism being humanity’s final form, because it doesn’t have to be. We can choose another path. But while we’re in it, there’s no doubt that our culture is stuck. Western civilization is seemingly out of compelling ideas (with a few exceptions), and it’s left me wondering if this is all there is, or at least all there will be because any alternatives have been deliberately destroyed. Are we really at the end of history, where our options are either an absolutely mediocre modernity or to traipse through the highlights of the mid-to-late 20th century?

In early 2020, Dua Lipa released one of the most acclaimed pop records of the year, Future Nostalgia. The album opens with an eponymous bop that confidently states:

You want a timeless song, I wanna change the game

Like modern architecture, John Lautner coming your way