I’m trying to be better this year. Not in a New Years’ Resolution kind of way that feels very official but also very trite, but in a way that feels more natural to me. It’s a process that actually began late last year, and has more or less happened organically, without quotas. There are goals, of course, but without any particular deadlines and with an understanding that I’m fallible and won’t go in a straight line towards where I want to wind up. I know the more official ways of doing these things can be successful for other folks, but I don’t think it’s for me.

Ok, that’s a lot of neuroticism. Words and justifications for those words. But that’s often what we do when we write, isn’t it? Basically, I feel like my life is hurtling towards a major shift and it’s making me reflective and wanting to make some changes. I finished my degree in December and later this year I’m turning 30. I’m constantly fielding questions about “what’s next” and it’s anxiety-inducing because I don’t know.

I guess from that not knowing is the starting point for what this essay is all about. I’ve lived my life in a particular way for the past several years, during university, and, in the last gasps of my 20s, I am tired of a lot of those ways. Well, in particular, I’m tired of the Internet and the ways it’s reoriented my life. I think a lot of people can relate to that, coming out of the covid-era of peak isolation where we didn’t see anyone except through screens (even though this trend was well underway in the 2010s).

The problem is I’ve invested a lot of my life into the Internet, and I’ve become reliant on its offerings. A lot of us have. Because of how deeply embedded the Internet has become (and will only continue to become), it makes it hard to detangle yourself from Internet addiction. Much of this is by design, such as the infamous slot machines of social media and reliance on navigation tools.

It’s not like the Internet is all bad. In truth there’s been a lot that I’ve gained through it. And many people can interact with the technology in a myriad of ways and come out unscathed. Sometimes I envy them. I think my personal concerns with the Internet are largely rooted in social media and the general ubiquity of always being on. This aspect of the Internet has been particularly detrimental to me.

I’m so tired of always being connected. I desperately want to log off and touch grass. So why don’t I? I initially wrote this essay with the seemingly-profound claim that I no longer care about the Internet. But I do. I want to not care, but I do. That’s the problem.

Recently, there’s been buzz about social media use and the rise in teen mental illness. The interesting thing is that the sharp rise in teen suicide and depression only started around 2012. Social media obviously predates this, despite the now-clear connection it has to rising loneliness and poor mental health. But, the early 2010s were when smartphones became the dominant cellular form and when things like front-facing cameras on phones became the norm. Noah Smith argues that this shows us that the Internet doesn’t have to be bad and that the way it’s evolved has allowed it to become more toxic. They note that the period between 1996 and 2006 saw a decline in teen loneliness, a time of rapidly expanding Internet access. Smith leaps to the idea that the old computer-centric Internet was a compliment to in-person socialization, but the always-connected nature of the mobile-first Internet has subsumed traditional IRL community and lead to ever increasing atomization. Instead of the Internet being an escape from the real world, Noah suggests that the real world has become an escape from the Internet. We’re now so embedded in various forms of the Internet to the extent that it’s become synonymous with our reality in ways that are truly unhealthy and at the expense of organic, natural interactions with community and reality.

This difference between the computer-centric and the mobile-centric Internet is something I’ve really picked up on in my own ways of understanding the Internet. Before I got my first smartphone in 2014, I may not have always had a good time on the Internet, but it wasn’t as bad as it is now. And when something bad did happen, it was confined to home (or school) and whenever I left the house, it didn’t follow me. I could also spend hours on the Internet and be sharp and focused, able to regurgitate article after article with ease. I was learning through the Internet, rather than letting it iron out the wrinkles of my brain. This prior Internet was a healthier learning environment and allowed for development of alternate communities that supplemented my real world ones (something Noah also talks about). I also find that the friendships I develop primarily in-person are less rocky on average than those that develop online, because I’m getting to know a person while experiencing their gestures, intonations, and general vibe. These relationships can be supplemented by a text message or two, but don’t live online.

One thing Noah misses is the political economy behind the current iteration of the Internet. Yes, the little black boxes in our pockets might be evil, but the story doesn’t end there. The Internet and smartphones don’t have to be evil, but how they’ve been developed and pushed onto us is. It’s also worth noting the socioeconomic instability that causes many to dive into their phones as well as the ways that these technological mediums are designed to emphasize negative content and thus make us feel worse as a way of driving engagement. A phone or Internet service doesn’t have to act this way, and perhaps if people could afford food they wouldn’t use their phone as a clutch of escapism.

Phones and social media as they exist today are tools reflective of our late-stage capitalist moment. They further the neoliberal agenda of extreme atomization and, in that alienation, sell us new ideas that fuel consumption and grow the economy on the backs of our loneliness, anxiety, and depression. PE Moskowitz uncovered this a couple years ago when they did a deep-dive into the Buzzfeed-ification of mental health. They found that one of the original founders of Buzzfeed, Jonah Peretti, fortold some of this back in 1996 when an undergrad. According to Moskowitz:

Summarizing Deleuze and Guattari, Peretti writes that capitalism breaks down codes, rules and social desires, scrambling the code of human behavior and the human mind so that it can replace these necessities with its own rules, codes and desires.

As capitalism dismantles inherent forms of community and connection, it replaces it with its own version of these things to fill the same, innate desires. Capitalism atomizes us and then sells us bastardized versions of the connection we’re lacking as if it’s just as good, if not better, than what once was. It evangelizes a doctrine of rabid individualism and self-centredness that compels us into commodifying ourselves to churn the wheel of everlasting growth forward and maintain the status quo. We’re marketing ourselves online in various ways to ostensibly build community, but in reality, we’re being conditioned to seek out an ersatz version of it that’s decidedly egocentric. This rewires our brains to seek brainless validation instead of community as the Capitalist Internet scrambles us and conflates the two. I mean, aren’t we all just so valid these days?

UK-based fashion retailer Bound argues on their Instagram page that they are “a movement of original contemporary wear; Togetherness in originality.” But really, their clothes are deeply embedded within the piping hot trends of patterned ‘70s polos and ‘90s striped shirts that you can find at endless online retailers these days. Their clothes are also not cheap by any stretch, rendering many unable to “come together,” masking an exclusivity that’s been veiled in inclusivity within this pretense of a community. The very notion of togetherness coming from purchasing their clothes is an absurd but very normalized rendering of the isolation that capitalism provides. By creating systems that disconnect us, capitalism has to fill the void, and does so in a way amenable to its imperatives around growth and consumption: by getting us to buy in a vain and hollow reference to some imagined community.

It’s no wonder that, in an age of heightened mental unwellness, there has been a rise in openness about that struggle that has been latched onto by the system and repackaged in a new wellness economy. Capitalism loves to consume its criticisms without meaningfully addressing the root cause. It hears that we are more depressed and anxious, and so it gives us Bell Let’s Talk, even though the telecom company has a track record of giving its employees panic attacks. Rayne Fisher-Quann recently published a brilliant essay critiquing the self-empowerment slant of online mental wellness culture. The core ideology of this movement is quite individualistic and argues for focusing on yourself because you don’t owe anyone anything. In self-empowerment, there’s often a focus on producing as little friction in life as possible. Isolate yourself, work on yourself, buy the right products to fulfill those ends, and come out a better (and more productive) member of society.

This ideology is convenient for everyone selling you on self-empowerment because instead of seeking deep connection with people, building community and solidarity, helping each other out, and so on, we can focus on ourselves and uplift ourselves with transactions. It’s the talkshow host brand of self help. Feeling sad? Buy this night cream to reduce the look of fine lines and crows feet. Not to get laid, but to feel empowered about yourself as an atom of society. No wonder everyone is beautiful and no one is horny (which we’ll get to later).

I’ve been seeking out new music lately, and sometimes a Megan Thee Stallion’s “Her” from last year pops up on my Spotify radio. The song’s as catchy as derivative ballroom-esque pop can be, but what really gets me is the opening lyrics:

I don't care if these bitches don't like me

'Cause, like, I'm pretty as fuck, hahahaha

These lines are indicative of and reinforce the hyperindividualism of late capitalist modernity. In the contemporary cultural moment, it doesn’t matter if you’re liked so long as you’re hot. Because you don’t owe anyone anything and they don’t owe you anything. And it also implies that you only need to be likable if you’re ugly. We can wax on about how nice Keanu is, but at the end of the day, it doesn’t stop the trend of self-centring that is propogated by social media and pop culture. With how central the visual platforms like Instagram and TikTok have risen to become, our worth has become increasingly tied to how we look, rather than how we act. To be liked on these platforms, you don’t need to be nice, you just need to have your buccal fat removed and get an upper blepheroplasty. Megan’s “Her,” like so many pop songs these days, reflects this mindset and fetishizes it.

But we do owe each other some things. We do need each other, too, perhaps more now than ever as a resistance to the atomization of society. Relationships are difficult, but the real world isn’t frictionless, and in that friction, we can grow, learn, and adapt in really awesome ways. Fisher-Quann eloquently stated: “we all exist to save each other. There is barely anything else worth living for.” I don’t know if that’s objectively true, but I still feel it in my marrow.

Life is aesthetic and nothing is authentic anymore. I deeply loathe how much it feels like our world revolves around chasing clout on some elusive algorithm. Business interiors are instabait while popular hikes are miniature movie shoots for TikTok. And I say this as a visual person, someone who gravitates towards the aesthetic. But there’s no substance to any of it and I’m tired of my world lacking substance. I’m worried it’s too late to reverse course on a collective level, but at least I can make changes for myself.

All of this is to say that the contemporary face of the Internet — social media and smartphones — have been on my mind a lot lately and I’m trying to recalibrate my use of both. I was promised an information superhighway and all I got was brain rot. Ok, maybe that’s a bit melodramatic, but that’s certainly how it feels at times. I have learnt a lot through the Internet and built many great relationships through it, and can recognize its utility, but the technology has been corrupted and thereby corrupted us in huge ways. Perhaps the biggest is that we’re all commodities in ways previously unimaginable. Not only is our data sold to the highest bidders even though it’s becoming increasingly apparent how little it helps advertisers and the like, but we are pushed into making ourselves a brand to be consumed. We’re compelled into marketing our lives and bodies in particular ways to gain anonymous validation in a way that obfuscates the real human need for genuine connection. Everything that winds up online melts into clout.

Social media, in particular, is all about clout. Clout for the sake of clout. Clout for financial gain. Clout for righteousness. We all do it. It’s why we post what we do, when we do. A hot selfie is an easy road to lots of red hearts. Or if you’re a little more “pick me,” maybe you get into a carefully crafted Story about some social justice issue to rant at your echo chamber about instead of doing anything meaningful to materially help undo marginalization. I’ve done both of these things because I crave that clout. It’s what Instagram et al are designed to make us crave and they’ve done a good job on me. When a post of mine isn’t getting as many likes, I may realize it’s probably the algorithm up to no good, but it still feels like a personal slight because of how Instagram taps into our emotions. It’s incredibly toxic. I don’t judge others for falling into the clout-chasing trap because I’ve been stuck in it for so long. It’s more a reflection of the sinister nature of big tech companies. Regardless, it’s all so fake and I’m exhausted by it.

I know none of these criticisms are particularly groundbreaking. I’m sure many of you have also been considering the negative impacts of social media. I’m not saying anything unique. I’m not being clever. I’m not even trying to be because doing so is just another way of trying to get hollow clout online. I know the futility in doing anything of worth on the Internet. The thing is that I don’t care if I’m clever or groundbreaking anymore. I just want to be, whatever that may be.

Freddie deBoer recently wrote about the “Bitter End of ‘Content,’” in which he discusses content explicitly designed to confuse viewers with incorrect or incongruent information as a way to manipulate people into further engagement (commenting their confusion, sharing with friends to see if their friends “get it,” rewatching to see if they can “get it”) and thus exploit the algorithm into giving them more clout. This is what our society has come to and it feels like such a waste of time and resources. Like, girls, we’re in a climate crisis and we’re wasting resources on this nonsense just to stroke our egos?

Remember how I’m trying to improve myself this year? Well, the first action in my one-sided feud against the contemporary Internet was deleting Twitter last December. Aside from Instagram and Reddit, it was the only other social media I still used. I got rid of Facebook in 2020 and TikTok in 2021. Snapchat and Tumblr I stopped using eons ago. Getting rid of the bird app was a very sudden decision that lacked any pre-meditation. I just felt like it was time and it unexpectedly became the beginning of a wider rethinking of my use of the Internet.

After a week or two of reflexively having thoughts that could be crafted into clever tweets and lamenting the lack of a place to put them, I found I didn’t miss much about Twitter. I also began wondering if years of crafting tweets in a particular vernacular that was conducive to virality (even though I was never successful at that) had rewired my brain into churning out thoughts in a particular way.

Twitter didn’t feel hard to get rid of, even though I stalled on doing it in the past. Everyone I knew on there I had other ways of keeping in touch with. It’s not 2009 and Twitter doesn’t really feel essential for online connection these days. With Elon Musk at the helm, it’s also only getting worse by the day.

You know what does feel essential, though? Instagram. I’m low-key convinced Zuckerberg hates how this silly photo filter app he bought wound up more successful at the thing he spearheaded with Facebook in the mid aughts. The problem with Instagram is that even if you don’t desire posting, it still feels necessary in order to keep up with what events are going on, check if a business is open during a holiday, and even communicate with people as it’s become the default messaging app for my generation. To leave Instagram means becoming someone regularly out of the loop. Thus, I still haven’t gotten rid of Instagram, but I’ve wound down my use of it since January. I decided I’d keep my account up, but stop posting. I’m able to keep up with the various accounts I follow and respond to DMs, but I don’t let myself have the short hits of dope that posting provides. Instagram’s by far the most toxic social media platform I’ve ever used and because of that, it’s one that’s going to be the hardest to entirely detangle myself from. However, I think I need to for me to regain some sanity, and reducing my use without cutting it cold turkey seemed like a decent first step. My goal is to ultimately delete Instagram, but that feels like too much of a leap right now.

And yet, I hate that I haven’t gone further and cut Instagram out completely. If any specific place was responsible for making my attention span shorter than a goldfish’s, it’s Instagram. The place that gave me FOMO, body dysmorphia, and only worsened my heightened emotionality. It taught me to hate the way I look and allowed me to routinely judge and feel judged. But, god, I’m so tired of comparing myself to others. It’s a deeply ingrained, automatic pasttime of mine rooted in the childhood trauma of intense bullying, and that embeddedness makes it hard to shake. Platforms like Instagram amplify the comparisons and make me feel like life’s a popularity contest that I could never succeed at. Everyone’s more successful, having more fun, and all around greater than I could ever hope to be, even if it’s all artifice.

I hate feeling like it’s impossible to leave Instagram. Jon Haidt recently published findings regarding the mental illness epidemic around teenagers and social media habits. He found that the focus many researchers have on findings are related to individual usage of social media. But what’s often neglected is the network effects these platforms have. If all your friends are on Instagram and use it heavily, you’ll be more likely to feel left out and ignored if you aren’t on it.

I notice this even without deleting Instagram. I feel like I lack object-permanence for a lot of folks. If I don’t post, I don’t exist. I feel the onus is more on me to reach out to people now because otherwise I’m forgotten. It’s incredible how conditioned we’ve become to needing to see someone post online to be reminded of their existence to engage with them. It’s amazing how much of our interactions are mediated by digital spaces that ironically exist to further atomize us from each other. We’ve become so reliant on replying to Instagram Stories for reaching out. I get it — I do it all the time — it’s incredibly low effort and sometimes I like its occasional ability to spark a deeper conversation. But still, maybe I don’t need to have object-permanence for 100 people, anyway. It’s a lot of noise to keep up with on my end, too.

Relying on Instagram to keep in touch is also a cheapened form of connection. Most of the time it doesn’t lead into something great even if sometimes it does. It’s easier to go for the instant dopamine of online interaction, as superficial as it can be, rather than expend mental energy on something more rewarding. Instead of using our available social energies on building deep connection and having real conversation, we’re replying to Stories, liking posts, and doing this for hours with countless people. Our energies get consumed by being consumed and consuming others. Everything is consumption because everything is clout. It’s like we’re competing to see who will win the contest of “Most Consumed.”

This is something that affects all of us, even those not on Twitter or TikTok or whatever comes next. My dad is known for being totally off of social media, despite repeatedly being pressured by friends to get Facebook for going on 15 years. And we’ve discussed how choosing to not be on these plaforms has negatively impacted his relationships with certain friends. People have become so used to using these platforms to tell their little world what they’re up to that they don’t know how to interact with those not online. Whether it’s not getting a meme or people forgetting to tell you big news because they just told everyone via socials, you do start to feel a bit out of sorts with the world around you when you disengage.

Perhaps I’m overthinking the cheapening of communication online — not every social encounter needs to be profound or deep. Sometimes a Story reply is all the energy we have and it satisfies our need to connect. But it still feels like we’re collectively losing something in our abilities to form community and connection by being overly reliant on these digital social platforms. There’s also a superficiality to a lot of online communication and people interact with each other in ways that would be considered rude or off-putting in real life, and yet it’s the main way we communicate now. A culture that tells us to only work on ourselves and not owe anybody anything is the same one that spawns ghosting, narcissism, and ignoring people’s engagements with you. I also think social media has conditioned us to want (or need) interaction all the time. Then, we’re too worn thin to have a genuine interaction with somebody. It’s ok to not always be plugged in and instead just be with yourself, your thoughts, and then preserve your energy for better socialization.

It’s funny, in winding down my social media use, not a lot has changed. The sparkle of righteousness that started me on this path is no longer fuelling me. I may be off Twitter, but I basically replaced that with Reddit (gross). I spend more time on YouTube, too, though at least that I only use at home on my computer. I may be doing less on Instagram, and that’s good, but it’s still around, which isn’t good. And then there’s the Substack of it all.

Remember how I said I was going to stop posting on Instagram? Well, I still wanted somewhere to have my photos, and decided I’d do an old-fashioned long-form photo blog as replacement. My initial plan was to use Wordpress, because I liked its customizability and detachment from anything resembling social media. I could even remove the like and comment symbols, which always seem to glare at me. But in my trial use of Wordpress, I kept having technical issues and then a friend said, “I don’t know why you didn’t just use Substack for this.” So, I did a quick switcheroo and now Memories of Geographies, my photo blog, is on Substack. This platform is a lot smoother and does a lot of the stuff I wanted and so I haven’t looked back since.

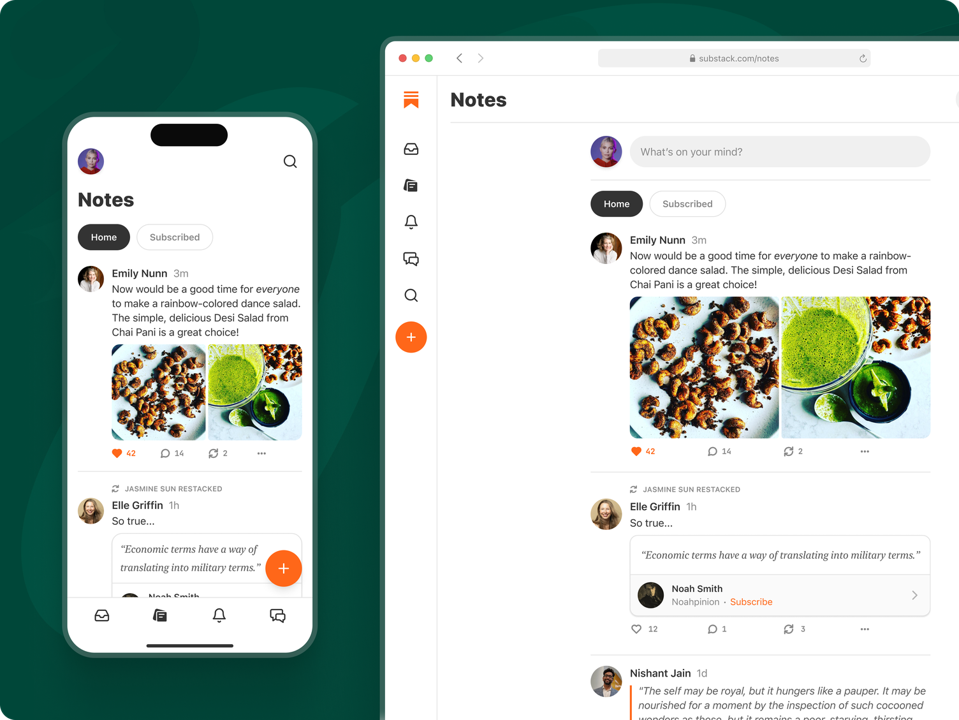

However, unlike Wordpress, Substack has an actual community of denizens engaging with one another. It’s funny, so many Substack users talk about this platform as if it’s some enlightened space that’s above and beyond what social media is. But, the truth is Substack is a kind of social media, just like Reddit and YouTube are kinds of social media, even though they lack the profile of Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. It’s interesting how TikTok easily gets labeled as social media even though most people on it aren’t actually doing anything different from YouTube (which often isn’t considered social media): passively consuming flickering visual fodder without posting.

And then Substack just straight up did classic social media with the launch of Notes. Remember what I was saying viz capitalism consuming but never fixing its criticisms, and instead shallowly offers new options that still perpetuate those criticisms? That’s what Notes feels like. But everyone on here is acting like it’s something greater, something more profound, something healthier than what we’re trying to eschew. No, we’re just doing Twitter all over again, like Instagram did with Snapchat in the mid 2010s. I’m still waiting on my Excel Stories, though. Any day now, I hear.

It’s kinda hilarious, but I was actually excited about Notes after Substack teased it a week prior to full launch. Then, it finally came out, and after about an hour of excitement, I started feeling horrible. Turns out creating a facsimile of Twitter doesn’t change the fact that it’s basically Twitter. It’s short hits of dope, it’s clout-y, and it’s everything I’m trying to get away from. The only major difference is that the community here is aggressively earnest.

This brand of militant sincerity that many Substack users cling to is cringe to the nth degree. It makes me want to gag. Not because being genuine is wrong, but because of how grossly artificial it all is. People on Substack talk a lot about how they want to get away from the attention economy and seem to want genuine online interactions with a community. They want the good of the Internet, the kind we had in the computer-centric iteration of yesteryear. I don’t blame them — I want that too and that’s also what attracted me to Substack. Because of the extremely earnest rhetoric on this platform, I’ve actually tried engaging with people on Substack in a way I generally don’t anymore on other platforms. It’s hard not to when the overall vibe is genuine and nice. I’ve commented on things to spur conversation or to try and see if people will come over to my Substack blogs because people seem very into discovering each other here. But you know what I found? Substack, both in Notes and in the Reader (which, for those of you who get e-mails, is the way us users read the posts of those we subscribed to), is just like Instagram and Twitter, but with a cheek-to-cheek smile of faux-earnestness throwing itself at you. You comment something thoughtful on someone’s new post and there’s no interaction. You see someone post a Note looking for new photographers to check out on this website and see they’re engaging with other people in the comments but not you. If I wanted to be left on read, I could just talk to people I already know. Yes, I’m mentally ill.

But, what’s behind the niceties? Clout-chasing. This place is chock full of people who want to get away from social media but are doing the exact same stuff to build an audience and gain validation. Substack users are being nice and genuine because they think it’ll win them new subscribers. This is particularly evident when you check r/substack and see everyone chasing subscribers like Instagram influencers chase followers. Writers and creators are only putting out offers of engagement and writing in a super friendly tone to build that list of follows. It’s so fake and that’s what makes me gag. What I really don’t like is how this mindset on Substack sucked me back into clout-y habits, the very thing I’m trying to get away from, by claiming to be different because… people are nice?

At the very least, I can be thankful for Notes showing the true nature of a lot of Substack’s virtue signal-y positivity in full view. It reminds me of why I want out of the rat race of social media, why I want to touch grass. Sometimes I think I should’ve stuck with Wordpress, but honestly there’s a lot of cool content on here, and it isn’t as toxic as the other places (yet). Plus, as it’s currently designed, it’s easy to just focus on yourself on Substack and write with abandon. You don’t actually need to open the Notes tab. It’s not like Instagram where everything is screaming at you the moment you open the app.

But wait, isn’t focusing on yourself bad? Didn’t I complain about that ideology, backing it up with citations? The thing about a lot of discourse is that it’s very black and white. Focusing on yourself can be bad, but so can letting yourself be consumed by others. The truth is in the nuance. There’s a balance between the two and what’s a healthy mix between yourself and those around you depends on the person. The main thing is that it’s important to take care of yourself and it’s good to do things for yourself, but you shouldn’t isolate yourself or chase rigorous self-optimization in doing so.

From my perspective, engaging and trying to build community on social media is rife with problems. The vast majority of stuff on these platforms doesn’t do anything but harm us. I don’t want to live my life like this anymore. I want to be real, not BeReal (lol). The Internet feels like a mistake. Even though it has a lot of good, practical uses, the way it has been built around the attention economy over the past 15 years plus has rotted us. Or at least it’s rotted me. There’s so much bullshit and it’s merely designed to anger us because it feeds engagement.

Even though I’m trying to not use Instagram much anymore (and truthfully, my usage is way down now vs the beginning of the year), I still feel addicted to it. When I’m bored, I will mindlessly open Stories, eyes glazed over, and not even really seeing what’s before me. The process has become automatic even as I’ve become more disillusioned with what winds up on Instagram. I’m a robot when I open the app. That’s the ironic thing about Instagram in particular. As we’ve collectively become more mentally ill, we’ve been more tightly curating what we post on places like Instagram. What used to be a silly app to post low-res, filtered snapshots of our food is now where we primp for the algorithm, hoping it will validate us, like some digital “mirror, mirror on the wall.” All of this is to say I don’t actually see a lot of my friends posting very often on Instagram and so it’s useful for other stuff, but social media feels most engaging when it’s personal. Even when I was posting on Instagram, I spent most of my time in the DMs. And I used posting to validate myself with the short hits of dopamine that I got from that little red heart lighting up repeatedly. My intent wasn’t generally that when I took a photo that wound up on the ‘gram, but morals go out the window when the upload button gets hit, didn’t you know that?

I’ve been thinking a lot about RS Bennett’s recent essay, “Everyone is Beautiful and No One is Horny” lately (told you we’d get back to it). She talks about the current state of mainstream cinema, and how actors are hotter than ever, impossibly perfect specimens of immaculate beauty, and yet their characters are sexless nevernudes. Bennett contrasts this with the Hollywood of yore — particularly the ‘80s and ‘90s — which, while problematic in its own ways, still featured people that looked like people. They weren’t unrealistic, surgically-modified action figures. They were gorgeous, but “still featured recognizable human bodies and human faces—bodies that could theoretically be achieved by a single person without the aid of a team of personal trainers, dieticians, private chefs, and chemists." A side effect of the crash diets that many actors go on, coupled with intensive workout regimens, is a reduction in libido. As Bennett states, “is there anything more cruelly Puritanical than enshrining a sexual ideal that leaves a person unable to enjoy sex?”

This arguably exists beyond cinema. Musicians get fillers too and Madonna’s alien facelift is definitely getting people talking, which is just another form of clout. Teenagers don’t even have an awkward phase in the development of their style because they have the Internet at their fingertips. Porn videos are clinical, rather than something actually hot, despite the impossibly hot specimens humping for our entertainment. The gritty gay porn magazines of the late 20th century had an authenticity to them because, while they had beautiful people in them, they still looked like people you would see in the real world. But as the Internet has subsumed the physical world, our ideas of what people ought to look like are increasingly informed by exaggerated standards that honestly feel exhausting to keep up with.

Sometimes, I fantasize about throwing my iPhone into the river and getting a so-called “dumbphone.” I really like the idea of that. I don’t know how realistic that is, though. I also like navigating and planning transit routes with Google Maps, being able to check the weather, and use messaging apps like Signal. I actually prefer messaging on my computer, but these apps are tethered to phone numbers instead of e-mail addresses these days. It doesn’t quite rub my brain the right way, but more realistic would be to strip my iPhone down to the barest of bones. Maybe I just want to be able to snap a clamshell phone shut after a call like it’s 2006 again. That sound was so satisfying. If you know of a dumbphone that lets me use Signal and Google Maps, let me know.

There’s so many other things I’d rather do with my time than waste my days on the Internet or glued to my phone. There are times I wonder how strange we must look like to our pets, staring for hours at inanimate black boxes as if we’re in a zombie version of 2001: A Space Odyssey. I’d like to take more photos, have engaging conversations, play board games, watch shitty reality TV, go dancing, experience new cities, maybe get into embroidery or linocutting, and read more books. I’m already doing some of these things, but I wish I could do more. The problem is that social media and rabid phone usage has rewired my brain and so these digital platforms are automatic patterns of behaviour that are hard to break because of their addictive nature. Like, there’s so many books I want to read, but I find it incredibly difficult to stay focused enough on something longer than a news article. And that’s generous — sometimes even a news article is too long.

In trying to better myself and “log off,” I realize there’s complicated, conflicting tensions that have to be addressed. I want to be better in order to live a life I want, in which I’m more present, engaged, focused, and so on. But also, it’s the year of our lord 2023, and everyone’s online and so much of our interactions are mediated online. Thus, it feels isolating to leave (thanks to network effects), despite feeling feel like I need to disconnect to really connect. And that’s on top of the fact that these platforms are almost necessary for communication now despite how much they focus on extreme individualism and exploit our fears and biases to further divide us.

I think my next move is going to be removing the Instagram app from my phone, such that I’m only able to check things when I’m not out, when I’m at my computer desk. I’ve been reticent towards this idea simply because I rely on the Story function still to share new Substack posts to non-subscribers who want to keep up. Despite Instagram making the desktop side of their platform more accessible and full-featured in the past few years, posting Stories is still one thing you can’t do without the iOS or Android app. But I also know that the app version of Instagram is a lot slicker and thus easier to get wrapped up in. I don’t really browse Instagram so mindlessly on my computer — I check my messages, use it to look up specific accounts (like if a business is open on a particular day), and briefly look at the feed before getting bored. The feed and explore pages are far less intoxicating on a browser. With this in mind, why should I sacrifice a healthy next step to stemming my social media addiction to do the thing I’m trying to not do — post (albeit in a less harmful way) — for the sake of others who may not even be that interested anyway. I’ve made it quite clear where I’m at now for months for those who are interested in keeping up with me. It’s hard to break the habit of being fixated with clout, though. I think that I frame this idea of wanting to ensure others are able to keep up to me as a convenient cover for clandestine clout-chasing endeavours. So maybe I should just stop. If I really feel the need to plug my Substack for those scant few who don’t want to subscribe, but want to keep up, can always just do a feed post telling people about it.

I need to let go of clout. I know my desire for validation and recognition in digital spaces stems from the trauma of intense bullying as a teenager. I was so deeply unpopular and so regularly debased by my peers for years. It’s hard to set that trauma free, but I really don’t want to be beholden to it anymore. I’m going to be 30 and I don’t need to constantly compare myself to others and I think I need to let go of the idea of being reachable by folks who may follow me but clearly haven’t taken that much of an interest in me over the many years I’ve known them. It just isn’t going to happen, and that’s ok. I don’t need their validation, and I know that, even though it’s hard to not want it. The Internet, as it’s currently oriented, has made me want it and it feeds my insecurities. I want to break that system.

Another aspect of my hangup over disconnecting is the idea that I’ll become more removed from my community. But am I really that connected as it is? Social media does a good job at making you feel like you are, but it’s all artificial. If you’re like me, you already know this, but we only show the sides of ourselves we want others to see. We curate ourselves to be amenable to consumption. These digital products are free to use because we’re the products. And so on. Once that splash of dopamine comes and goes, I don’t really feel all that more engaged and present in my community. Instagram doesn’t do that for me. Getting drunk with my friends and being silly does. Or having a deep conversation with someone at 3 in the morning. Or experiencing something with someone together, whether that’s a hike or a movie or a show or a class. So while the networking effect of social media is strong, and if I continue on this path, there’ll definitely be moments in which I feel more isolated, I do truly believe in the long run I’ll be healthier for having a more arms-length relationship with the Internet.

One thing’s for sure, though — Instagram’s gotta go. That bitch is toxic.